If he had lived, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw would certainly have been the most handsome Civil War general, for his beautiful face and his gallant heart.

Robert Gould Shaw (1837 – 1863) commanded the 54th Massachusetts, an all-Black regiment in the U.S. Colored Troops of the Union Army. (Although the U.S. Colored Troops did have a handful of Black officers, leadership of troops was by white officers.)

Shaw fought not only the Confederates; he fought the Union, pushing for equal treatment and equal pay for his troops. In early letters from the War, he referred to Blacks as “darkeys.” As his understanding of and trust in the soldiers grew, he evolved to use “Colored,” then the most respectful term for Black people.

With Charlston as the ultimate objective, in July 1863 the Union set its sites on Fort Wagner, which defended the southern approach to the harbor. The 54th was deployed. The Union underestimated the strength of the defense and lost the battle. However, the valor of the 54th Massachusetts under overwhelming fire from the fort inspired enlistment of Black men throughout New England. Shaw himself was shot to death at a parapet of the fort.

Customarily, the enemy returned officers’ bodies to their side. In a calculated insult by Confederate General Johnson Hagood, Shaw’s body was buried in a mass grave with his men.

Shaw’s abolitionist father saw it as an honor: “We can imagine no holier place than that in which he lies, among his brave and devoted followers, nor wish for him better company. – what a body-guard he has!” (quoted in Shelby Foote’s The Civil War: A Narrative)

The blog Written in Glory provides a fascinating chronological selection of letters by the soldiers and officers, including Robert Gould Shaw, of the 54th. (Given that the letters were posted day by day during the Civil War sesquecentennial, the earliest letters are the blog’s earliest posts.)

Two poems offer views of Shaw and the 54th in context of the poets’ own times. “Buried with His Niggers,” by Elizabeth B. Sedgwick, was published in National Anti-Slavery Standard (31 October 1863). Written nearly 100 years after Sedgwick’s poem was published, “For the Union Dead,” by Robert Lowell, has at its center the Memorial sculpture on Boston Common. Lowell first read the poem at an arts festival in 1960.

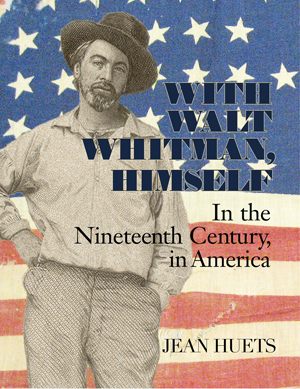

WITH WALT WHITMAN, HIMSELF: IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, IN AMERICA | by Jean Huets

“A true Whitmanian feast—for the intellect as well as for the eyes.” — Ed Folsom, editor Walt Whitman Quarterly

Amazon | B&N | bookshop.org (supports indie booksellers)

signed copies, free shipping order from Circling Rivers

“A beautiful book of windows onto the life of Walt Whitman…. From the clear ringing prose to the fascinating photographs and colored illustrations of the great poet’s life we find the man anew—standing in his time and looking straight at us. [Huets] has made a book of marvels and I can’t put it down.” — Steve Scafidi, Poet Laureate, Virginia

Explore the fascinating roots of Whitman’s great work, Leaves of Grass: a family harrowed by alcoholism and mental illness; the bloody Civil War; burgeoning, brawling Manhattan and Brooklyn; literary allies and rivals; and his beloved America, racked by disunion even while racing westward. Over 300 color period images immerse the reader in the life and times of Walt Whitman.