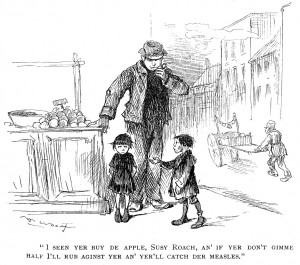

Nineteenth-century memoirs, letters, newspaper stories, and novels in the US were loaded, and sometimes larded, with American dialect.

Civil War U.S. Navy paymaster William Keeler quoted a black man boarding the Monitor: “O, Lor’ Massa, oh don’t shoot, I’se a black man Massa, I’se a black man.” A NYT Disunion writer said of Keeler that he “seemed to see the incident as little more than an opportunity for deploying minstrel-show stereotypes,” yet Whites of the time were near as likely as Blacks to find themselves speaking in dialect.

American dialect then as now came in all shapes and sizes.

Rufus R. Dawes of the Wisconsin Iron Brigade quoted a German Captain Hauser gazing upon green troops: “Vell, now you looks shust like one dam herd of goose.” An Irishman nicknamed “Tall T” –who was, of course, very short–had pantaloons so oversized they “would almost button around his neck.” “‘Who’s your tailor, Tall T?’ once shouted a man as we marched. ‘The captain, be gob,’ came back like a flash from Tall T.” The enemy spoke dialect, too: “We uns durst leave our mammy,” one “Johnny” mocked Dawes, “You uns is tied to granny Lincoln’s apron string.”

An Indiana farmer retrieving the body of his son in Virginia says, in a letter by Union officer Theodore Lyman, “And that old hoss, that was his; the one he was sitting on, when he was shot; she ain’t worth more than fifty dollars, but I wouldn’t take a thousand for her, and I am going to take her home to Indiana.”

An anthology of Southern sentiment, published in 1867, quotes an “Old Lady”: “Dr. Jones, he wus sent for, and he up and said the boy must have nothin’ exceptin’ it war gruel for as many days, as he wur out in the woods.”

Yankees came in for it, too. Lyman quotes General Seth Williams: “’Sir!’ says ‘Seth’ (who cuts off his words and lisps them, and swallows them, and has the true Yankee accent into the bargain), ‘Sir! The Pres’dent of these Nited States has issued a procl’mation, saying nothing should be done Sundays; and Gen’l Merklellan did the same, and so did Gen’l Hooker; and you wanter talk business, you’ve got’er come week days.’”

Frank Wilkeson, remembering his own meeting with General Williams, makes no comment on the general’s accent and quotes him in straight English. Still, Wilkeson couldn’t resist a touch of dialect in dialogue with a Confederate prisoner. “[He] inquired kindly, ‘Howdy?’ So I said, still seated and sucking my pipe, ‘Howdy,’ as that seemed to be the correct form of salutation in Virginia.”

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is dialect from start to finish, from boys to belles to blacks to bums. Samuel “Mark Twain” Clemens felt the need to offer guidance: “In this book a number of dialects are used, to wit: the Missouri negro dialect; the extremest form of the backwoods Southwestern dialect; the ordinary ‘Pike County’ dialect; and four modified varieties of this last. The shadings have not been done in a haphazard fashion, or by guesswork; but painstakingly, and with the trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several forms of speech.”

Though not free from the reflexive racism of their time, Lyman and Dawes used dialect even-handedly and apparently to amuse not abuse. On the other hand, Thomas Morris Chester, the only Black Civil War correspondent for a major newspaper, reported faithfully the stories of African American soldiers and civilians, avoiding heavy dialect while capturing the voices of his subjects. In Richmond, April 1865, he described the exultation of the people greeting Union troops. “The pious old negroes, male and female, indulged in such expressions: ‘You’ve come at last’; ‘We’ve been looking for you these many days’; ‘Jesus has opened the way’… ‘I’ve not seen that old flag for four years.’” Chester did not mine humor in the speech of his subjects, white or black. Read more on Thomas Morris Chester

The most authentic dialect, of course, is written by the speakers themselves, especially men uneducated, untrained to write other than as they spoke. From a Piedmont North Carolina soldier’s letter to his wife: “You rote to me that you was agoing to have a garden….” My great aunt, from the same area, used “a-” in continuative tense. Read more on North Carolina Civil War love letters

In a sense, dialect says as much about the writer as it does about his or her subjects; characters who speak dialect are those with origins and/or education differing from the writer’s. This is as true today as it was in the Civil War era. A Pennsylvania friend living in Ardmore, Oklahoma, found the response locals make to an introduction humorous. She hadn’t been living there long enough to know that what sounds to her like “Howdy-do” is really “How do you do?”

Context plays a great role, but reaction to dialect can also reflect readers’ preconceptions. Does a Southern White man saying “you uns” instead of “you” or a Black man saying “dat” instead of “that” evoke a positive or negative judgment? Or do you simply “hear” it as someone talking the way they talk?

William Keeler, “Ironclad Freedom,” Opinionator blog, New York Times / Theodore Lyman, Meade’s Headquarters, 1863-1865 / W.B. Lawson, Jesse James, the Outlaw / Rufus R. Dawes, A Full Blown Yankee of the Iron Brigade, pp 13, 47 / R.J.M. Blackett, Thomas Morris Chester: Black Civil War Correspondent, pp. 290, 297 / Frank Wilkeson, Turned Inside Out, p. 140, 144 / Old Lady, The Land We Love, p. 155 / NC soldier / picture via

Very nice piece. I like Lyman a lot, by the way. People quote him, but he doesn’t really get his due overall.

Thanks! I’m reading Lyman now (slowly, on my phone). He writes with that arch humor that seems so quintessentially 19th century.

Pingback:Thomas Morris Chester & racism in the ranks | JEAN HUETS

Pingback:Civil War Love Letters | JEAN HUETS