“The Richmond Times of October 18, 1864 reported that the Manchester [Virginia] town bell would be rung three times a day to remind people to take their quinine.”

Malaria remains a critical health issue, with about half of the world’s population at risk, according to the World Health Organization. The disease is no longer endemic in the United States but in the nineteenth century it was. Eminent sufferers include Abraham Lincoln, U.S. Grant, and Jefferson Davis.

The parasite that causes “ague” was not identified until 1880, and the mosquito’s role in transmission was not demonstrated until 1897. A Civil War era Scientific American article stated, “There is no doubt…that malaria is some mysterious poison in the atmosphere….” Blaming “miasma” has a grain of truth; mosquitos are more likely to be doing business at night, and in swampy, damp regions.

Quinine’s efficacy, at least, was long-known. In 1805, Dr. Washington Watts of Manchester, Virginia, treated James Scott with “papers of bark” (quinine derived from the bark of the Peruvian cinchona tree). Scott might have spared himself the expense (for which he was later sued). A physician was not needed to procure quinine. Laurence Bataille, in August 1827, ordered the medicine himself: Gentlemen, Mrs. Battaile has had an attack of the ague & fever – You will oblige me by sending by the bearer a phial of Quinine. Though formulations abounded, the bark could be eaten simply, “by placing it directly on the tongue, as, though bitter, it is a clean bitter, not unpleasant to most people.”

Arsenic was considered an effective, but unfortunately deadly treatment. Less effective but more pleasant remedies were on offer. In May 1862, the Richmond Times-Dispatch scoffingly quoted a letter written by a soldier in “McClellan’s army” and published in “the Northern papers”: “Whiskey rations are now served out to the soldiers morning and evening, to counteract the influences of the malaria.” Other regiments in the Army of the Potomac fared better. Scientific American reported that, whilst in the “malarious” region of the James River, men who took quinine daily during August, September and October “showed a remarkable exemption from disease.”

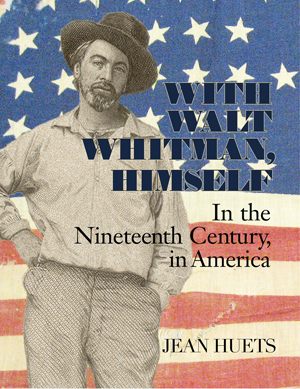

WITH WALT WHITMAN, HIMSELF: IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, IN AMERICA | by Jean Huets

“A true Whitmanian feast—for the intellect as well as for the eyes.” — Ed Folsom, editor Walt Whitman Quarterly

Amazon | B&N | bookshop.org (supports indie booksellers)

signed copies, free shipping order from Circling Rivers

“A beautiful book of windows onto the life of Walt Whitman…. From the clear ringing prose to the fascinating photographs and colored illustrations of the great poet’s life we find the man anew—standing in his time and looking straight at us. [Huets] has made a book of marvels and I can’t put it down.” — Steve Scafidi, Poet Laureate, Virginia

Explore the fascinating roots of Whitman’s great work, Leaves of Grass: a family harrowed by alcoholism and mental illness; the bloody Civil War; burgeoning, brawling Manhattan and Brooklyn; literary allies and rivals; and his beloved America, racked by disunion even while racing westward. Over 300 color period images immerse the reader in the life and times of Walt Whitman.

See more, on harvesting quinine.

Sources on Quinine: p 37, Old Manchester, by Benjamin B. Weisiger III | Scientific American CW era malaria | 1862 RTD | Oct 1865 Scientific American | photo via University of Virginia

Pingback:Social determinants of health in 10 figures – Global Doctors