Nineteenth-century women tended toward flowery scents, but a man could wear “violet water” without being considered effeminate.

Until the twentieth century, people tried to improve their body odor strictly by addition (applying perfume, cologne, toilet water), rather than subtraction (deodorant or anti-perspirant). Some scents were home-made from flowers, herbs, spices, and other botanicals such as orange peel and cedar bark. “Deodorized” alcohol (for example, whiskey redistilled with chemicals, such as permanganic acid), also called “pure alcohol” or “cologne spirits,” was the solvent and could be obtained from a pharmacist. Anyone who’s lived through a “blend it yourself” scent fad knows that many of these experiments ended up watering the plants rather than a young man’s or woman’s neck.

click to Tweet: #19thCentury #perfume @JeanHuets http://ctt.ec/0FyzR+

Florida Water (not a brand, but a kind) was popular for decades before and after the American Civil War. R.S. Cristiani’s 1877 formulation calls for oils of: bergamot (from the peel of the fruit, also scents Earl Grey tea), orange (probably bitter orange), lavender, cinnamon, cloves, tinctures of orris (iris root; similar in scent to violets and also used in “dentifrice” and mouth wash) and Peru balsam (unfortunately, a skin irritant), spirits and water. I take it that there’s more; surely Mr. Cristiani did not divulge all his ingredients. Other formulations from rival makers could include lemon, neroli (from bitter orange flowers), musk, and/or rose water.

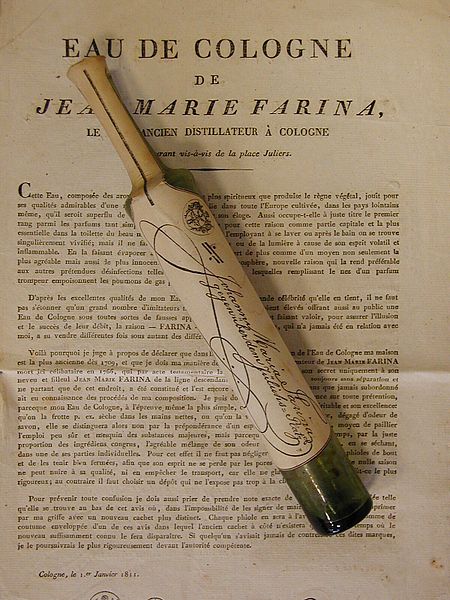

Some of the French perfumes that became great decades before the Civil War are still made today. One of my favorites (at least by the ingredients; I’ve never had a chance to try it on) is Jean Marie Farina’s Eau de Cologne, developed in 1708 (now in the house of Roget & Gallet). The scent has lemon, bergamot, neroli, rosemary, petitgrain (from bitter orange twigs and leaves; woody and somewhat floral), myrtle (probably the leaves; somewhat camphorous and just slightly floral), cedar wood, and sandalwood. Farina described it to his brother in 1708: “I have found a fragrance that reminds me of an Italian spring morning, of mountain daffodils and orange blossoms after the rain”.

“Perfume” was used medicinally to revive the faint and cleanse the infected. An 1864 “aromatic vinegar” composed of acetic acid, camphor and clove oil was called a “pungent and reviving perfume.” Blends of fragrant oils, including good old lavendar and bergamot, were used in smelling salts to retain ammonia’s pungency, which otherwise would dissipate too quickly.

Incidentally, bergamot the fruit used in perfume and tea is not the same as bergamot the flower, aka bee balm (Monarda). Bee balm flowers are pretty and easy to grow. Supposedly the leaves can be used for tea, but in my hot, humid southern garden, the leaves get unpalatably moldy.

WITH WALT WHITMAN, HIMSELF: IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, IN AMERICA | by Jean Huets

“A true Whitmanian feast—for the intellect as well as for the eyes.” — Ed Folsom, editor Walt Whitman Quarterly

Amazon | B&N | bookshop.org (supports indie booksellers)

signed copies, free shipping order from Circling Rivers

“A beautiful book of windows onto the life of Walt Whitman…. From the clear ringing prose to the fascinating photographs and colored illustrations of the great poet’s life we find the man anew—standing in his time and looking straight at us. [Huets] has made a book of marvels and I can’t put it down.” — Steve Scafidi, Poet Laureate, Virginia

Explore the fascinating roots of Whitman’s great work, Leaves of Grass: a family harrowed by alcoholism and mental illness; the bloody Civil War; burgeoning, brawling Manhattan and Brooklyn; literary allies and rivals; and his beloved America, racked by disunion even while racing westward. Over 300 color period images immerse the reader in the life and times of Walt Whitman.

Sources: Perfume Projects / Thompson Alchemists / Perfumery and kindred arts: A comprehensive treatise on perfumery, by Christiani / A treatise on pharmacy, by Edward Parrish, 1864 / “On the preparation of smelling salts” by A. Allchin, a paper read, reported in The Chemical News and Journal of Physical Science, April 20, 1861 / On orange blossom as the “pig of perfumery” see Perfume Shrine’s entry / NY Cloisters Museum garden blog Orange Blossom Special. (Orange Blossom Special was originally a passenger train inaugurated in 1925; dictionary.com gives this nugget: Meaning “special train” is attested from 1866.)

Fascinating. Always reading about Custer’s and Pickett’s “perfumed locks” but never delved deeper into it

I wonder what scent? Violets? Florida water? I imagine something rather sweet for Custer. Pickett, maybe something more like patchouli.

I have a question based on this article. I’m doing a project based on it and I would like to know who sponsors this website and also who is the author of this article?

Jean Huets is author of this article (and website). No sponsor for the website; this is my own website. For more info about me, see sidebar “about Jean Huets”. Thank you for your interest.

Awesome post.