A 32-page book written and published by the Arizona Territory Legislature in 1871 begins: “It is customary and generally considered to be to the interest of new countries, to conceal as far as possible the hardships and dangers necessarily incident to their first settlement, with a view of inviting immigration and capital as rapidly as possible, and thereby overcoming these obstructions.” One danger in Arizona, however, overcame that interest: the Apaches.

Memorial and affidavits showing outrages perpetrated by the Apache Indians, in the Territory of Arizona, for the years 1869 and 1870 was submitted to Congress as a protest against the reduced Federal military presence and as an appeal: “confidently believing that, when these facts are known, the press, the people of the United States, and the Government will demand and aid in subduing our hostile foe, and thereby reclaim from the savage one of the most valuable portions of our public domain.” The reduced military presence also threatened local economies that depended on trade with the military, just as localities today suffer with closures of military bases. (And as happens today, the press is mentioned as a not-subtle threat to politicians.)

The book paints Arizona as a land of milk and honey, with “nearly every mountain threaded with gold, silver, copper, and lead”, perfect pastures, perfect farm land, vast forests, and a climate “warm, congenial, and healthful.” The serpent in this Garden of Eden, according to the “memorialists” is “the subtile Apaches.”

The writers cite ruins of a previous native population. Although they admit “no one knows who they were,” the “remains of large irrigating canals” evidenced “a people of industry and enterprise” whose destruction was “undoubtedly the ravages of the implacable Apache.” If the U.S. would not send sufficient troops, the book warns, American settlers “only await a similar fate.”

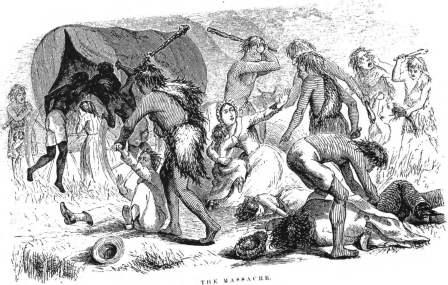

The rest of the book prints testimony of killings and thefts, given by over 100 farmers, freighters, ranchers, stage-coach station masters, military, merchants and others. Some detail grisly attacks.

A farmer, Jesus Ma. Elias, swore that in June 1869 he saw, “forty miles north of Tucson, two men, after they had been murdered, stripped and horribly mutilated by Apache Indians.” How he knew the men had been attacked by Apaches is not detailed; presumably the mutilations convinced him.

“JOHN G. BOUEKE sworn, and says he is 2d Lieutenant 3d Reg’t U. S. Cavalry testified: In September, 1870, while in pursuit of the Indians that captured the overland mail, he found two skulls that appeared to have been burned; also found a scalp.… Three weeks afterwards a party of prospectors were attacked fifteen miles from Camp Grant, by about sixty Indians, capturing horses, wagon, provisions and all they had, and wounding three men.”

The next spring—probably around the same time that Memorial was being printed in San Francisco—Camp Grant would be the site of a horrendous massacre of Apaches, mostly women and children, who had surrendered to the U.S. and were living on a compound under military supervision. The massacre was perpetrated by Americans, Mexicans, and Papago / O’odham Indians. No one was convicted.

Some of the “outrages,” some scholars believe, were perpetrated by American settlers in such a way that the Apaches would be blamed. The alleged motive was to escalate hostilities, so that the U.S. military would subdue and remove the Apaches once and for all, and to encourage settlers to take matters into their own hands—as they did at Camp Grant.

Read Memorials at archive.org . More on the Camp Grant Massacre, Picture source Our Arizona History.