“The laborers about the wharfs, when not negroes, were almost without exception Irish….”

In his 1910 memoir, Chicago journalist Frederick Francis Cook cites the collision of race and class to explain what he perceived as Irish immigrants’ opposition to abolition of slavery:

Nine-tenths of all immigrants [before the war] from the Green Isle were at best adapted only to the commonest labor, and so came often not only in close contact, but even in direct competition with blacks, both bond and free…. The laborers about the wharfs, when not negroes, were almost without exception Irish. The latter at this time constituted everywhere, North and South, the lowest white strata in the active labor market; hence there arose among them an intense desire to keep the negro in his place as slave…..

Cook praises the Irish for fighting pro-Union, but relies on stereotype to bolster his case that Irish-Americans opposed Emancipation. [ Read more on the Civil War Fighting Irish. ]

…Another motive to swing the Irishman to the Southern side suggests itself, namely, his natural affinity with the easy-going, toddy-drinking Southerner….

The Irish even took the blame for the 1871 Chicago Fire. (While the fire did seem to have started in the O’Leary barn, the real culprits were the tinderbox makeup of the city and the inability of its fire department to battle the blaze. Mrs. O’Leary and her cow were cleared in the official investigation–though not by journalists and historians.)

Cook derides the followers of Irish politicians with a racial slur: “the [newspaper men] assigned to report the [rallies]…were forced to the conclusion that either all Irishmen, like coons, ‘look alike’ or that they had seen these particular sons of Erin many times…” (Cook might have intended the “look alike” barb as facetiously crass; he generally reads as sympathetic to African-Americans.)

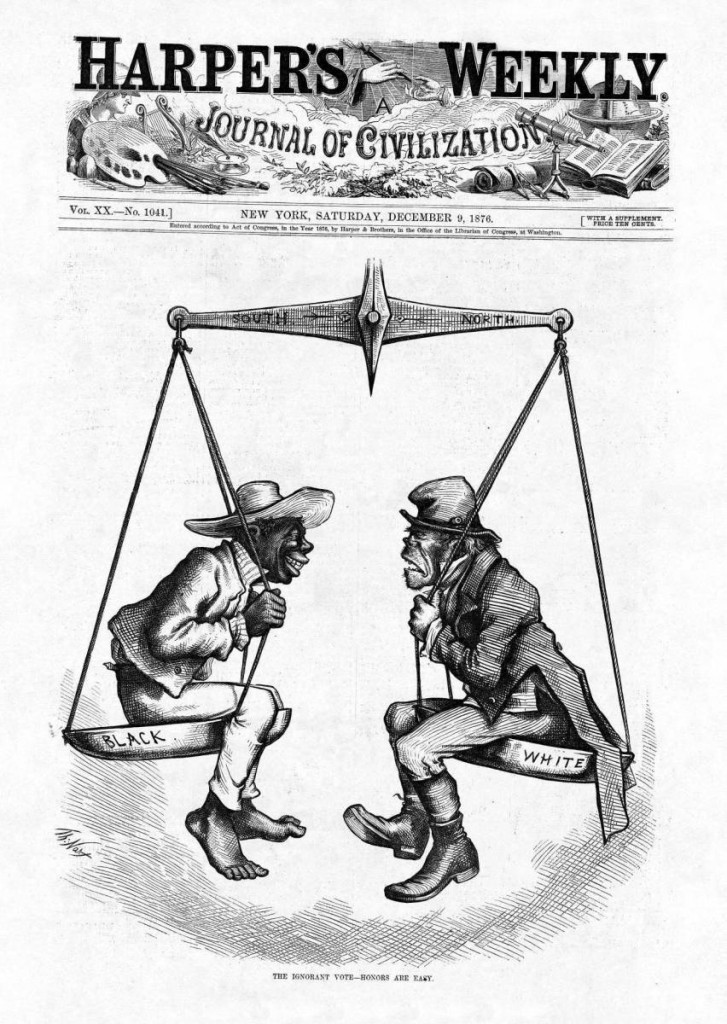

Seen as foreign, black-like, Southern-like, and poor: the luck of the Irish didn’t keep Irish immigrants from being one of the most maligned groups in mid-19th century America.

If you can get past Cook’s biases (mostly pooled in the first chapter), his book makes a vivid recollection of pre- and post-War Chicago. Or as people in Chicago see it, pre- and post-Fire.

Frederick Francis Cook, Bygone Days in Chicago, 1910. Nast Portfolio. Illustration via Harpweek.com

New York Times: Disunion (Civil War) articles by Jean Huets: The Iron Brigade | The Union Dead | Blood in the Carolina Hills | The Fall Line’s Fault | Boxers, Briefs and Battles | Killing Time: Playing Cards in the Civil War

An interesting snippet of history. Thanks for sharing, Jean. And thanks for stopping by my blog. You’re post was insightful.

Thanks, Kiru. I generally follow my curiosity on this blog. Sometimes it leads me to issues that continue to haunt “civilization”–in this case, the misery and ugliness of intolerance and bigotry.