The unlimited and easy procurement of opiates troubled 19th century pharmacists….

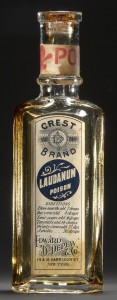

Opium was a must in the pharmacy of the nineteenth century, as a painkiller, obviously, and for many other ailments: delirium tremens, spasms of the bowels, toothache (“used as a friction on cheek or gum, as well as applied to the teeth”), “hooping-cough” in children, asthma, rheumatism, epilepsy, insomnia, anxiety, diarrhea…. The list goes on. The substance was dispensed in many forms, from eye drops to gummy pills to salves, and in combinations with sherry, brandy, and medicinal spices and herbs. Laudanum (powdered opium, water, and alcohol) was the most common preparation.

Doctors and pharmacists, and probably most lay people, were well aware of opium’s not so medicinal use as an intoxicant. In his 1864 Treatise, Parrish lists types of addicts: “Females afflicted with chronic disease; widows bereft of their earthly support; inebriates who have abandoned the bottle; lovers disappointed in their hopes; flee to this powerful drug…to relieve their pain of body or mind, or to take the place of another repudiated stimulant.” (Tangent: An example of the sentimentality of Victorian prose: you won’t find “lovers disappointed in their hopes” in today’s scientific treatises.) Most specific cases of addiction Parrish cites are women; surveys conducted in the 1870s show that women made up the majority of recreational users.

*** More Civil War era (New York Times) articles by Jean Huets: The Iron Brigade | The Union Dead | Blood in the Carolina Hills | The Fall Line’s Fault | Boxers, Briefs and Battles: Underwear in Service | Killing Time: Playing Cards in the Civil War ***

Unfortunately, users didn’t necessarily know they were imbibing. Patent medicines didn’t list all ingredients, and even a good old pint of beer could be adulterated. “The cupidity of fraudulent brewers,” says Cooley, led them to dose beer to “give intoxicating properties.” Parrish puts the responsibility squarely on physicians for continuing to advise opiates “until it has become almost impossible to desist from the indulgence.”

Before opiates became controlled, addicts male and female could feed their habit simply by going to their local pharmacist. If a pharmacist didn’t like that, habituees could go to competing shops “in the outskirts of our large cities” that specialized in low-priced laudanum. In 1878 Manchester, Virginia (now part of Richmond), “a druggist reported that one individual used about 120 grains of morphine a week (a huge dose). He said there was more opium sold in Manchester than in any city of the state. He stated that there was a man in Chesterfield County who drank a gallon of laudanum…every two weeks.” In 1902, Manchester pharmacists were still lobbying for local ordinances to regulate opiates.

The Federal 1914 Harrison Narcotic Act decreed that physicians could prescribe opiates only for medical conditions. Sadly, addiction was excluded, thus stimulating an entire criminal class to exploit addicts, many of whom, until the Act was passed, were law-abiding, functional members of society who had become addicts on advice of their physicians.

With over 300 period images and text with extensive quotes by Walt Whitman and his family and friends (and enemies), WITH WALT WHITMAN: HIMSELF immerses the reader in Walt’s tempestuous life: a family harrowed by alcoholism and mental illness; the bloody Civil War; burgeoning, brawling Manhattan and Brooklyn; literary allies and rivals; and his beloved America, racked by disunion even while racing westward. “A true Whitmanian feast—for the intellect as well as for the eyes.” — Ed Folsom, Editor of Walt Whitman Quarterly Review | MORE INFO |

Sources: Cyclopaedia, by Arnold James Cooley / preparing laudanum, dope shops: A Treatise on Pharmacy, by Edward Parrish, 1864 / Feb 23, 1878 The State newspaper article quoted in Old Manchester & Its Environs, by Benjamin B. Weisiger III / surveys re women: Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America, by David T. Courtwright / photo via NIH / Any mistakes are my own.