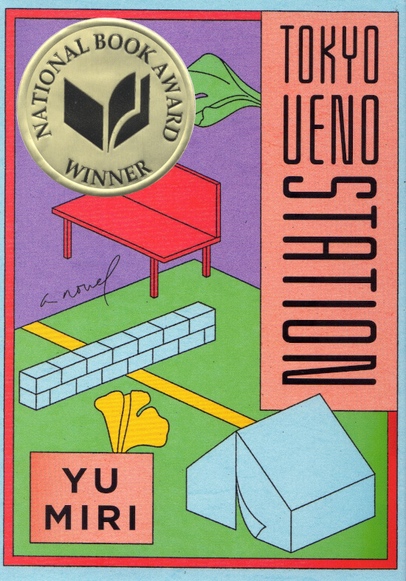

Tokyo Ueno Station, by Yu Miri, translated from Japanese by Morgan Giles

Riverhead Books, 192pp

BUY: bookshop.org | indiebound | amazon US

This book drew me not by its sticker proclaiming it a winner of the National Book Award, but rather by a New York Times article, “Her Antenna Is Tuned to the Quietest Voices.” The article described the author’s background, one of dislocation and sorrow, and how the book came to be.

First published in Japan in 2014, Tokyo Ueno Station draws from interviews Miri conducted with homeless people in Tokyo’s Ueno Park. The interviews took place after the vast dislocations caused by the 2011 triple disaster of earthquake, tsunami, and subsequent nuclear power plant meltdown. (The camp has since been shut down in preparation for the 2020—or rather, 2021, Tokyo Olympics.)

Of herself, Miri says, “I’m kind of like a parabola antenna, so that I can magnify the small voices of people who aren’t often heard.” The voice Miri amplifies in Tokyo Ueno Station is one that certainly wouldn’t be heard in our over-amplified world of disembodied voices. It’s that of a ghost, a very humble ghost, whose eyes, when he was alive and working, were turned to the earth, but who saw much more, especially after he elected to become homeless rather than burdening his young granddaughter with his care.

The humility of the narrator. His raw honesty. The simplicity of his observations. The poverty of his desires and of his life—he lived away from his wife and children in order to support them as an itinerate manual laborer. The place he lives, or rather, lived: a homeless camp that can be displaced at any time by, say, a 15-minute drive through the park by the imperial family. A place where a hot bath is a comforting luxury paid for by 300 cans collected for recycling. A place where the circumstances that led to someone living under a tarp create an unfathomable loneliness. The way a ghost might feel…

The wind whips around, rustling through the leaves of the trees, and now I can see the tent city full of homeless people. It’s surrounded by a green fence with a tarpaulin over the grating. There’s a design printed on the tarp—of a blue sky with seagulls and big columns of clouds floating, a hill with two trees, a two-story house with a red roof and smoke coming out of the chimney and two white-spotted dogs running toward it, but there are no people in the design.

The three sparrows that were perched on the lamppost before have now gone. I am haunted by this day, today, and regardless of what I am now, I would have liked to exchange a glance with someone, anyone, even a sparrow.