Historians writing about General Benjamin Butler love to point out his not-ready-for-Hollywood personal appearance. “His features were brutish,” Adam Goodheart says in 1861, adding a bit of psychological analysis: “inwardly, he nursed the outsize vanity of certain physically ugly men.” (It’s a lame generalization in an otherwise good book: “inwardly, he nursed the outsize vanity of certain [fill in the blank with anything at all; tall, short, fat, thin, etc] men.”)

True, Butler’s conduct could be ugly. As military commander over New Orleans, he issued General Order No. 28, which decreed that a woman could be treated as a prostitute if she insulted a Union soldier. The universal disgust aroused by the Order earned Butler the nickname “Beast” and, together with Butler’s ham-handed relations with civil authorities and questionable financial dealings, surely damaged the Union cause.

Yet — would the nickname “Beast” have stuck to a more dashing fellow? I can’t help wonder how history would see Butler if he’d had a movie-star visage.

Let’s pose a few true Butler stories against the “Beast.”

In 1856, when the floor of the building at a crowded political rally threatened to collapse, Butler averted a fatal stampede by calming the panicked crowd and directing them out.

His letters to his wife reveal a tender and attentive husband. “Be you sure to write me every day,” he implored from New Orleans, “— long letters as little sad as possible, and portray the shades of your mind — and not sad at all about me, for in truth you have no occasion.” And from Petersburg, “How are you feeling — cheerful and happy? Indeed and indeed I think you ought so to do; if a husband’s deep, deep love will be of any avail to make one happy. Write me every day, dearest, do.”

Grant hagiographers enjoy posing Benjamin Butler — a lawyer and politician who “earned” command by political appointment — against their bluff, West Point educated hero. (Grant was also winner of Most Handsome CW General contest here.) Butler certainly did not rival Grant in military prowess. But he did secure the wavering cities of Annapolis and Baltimore, Maryland, for the Union in May 1861, and in June secured Fort Monroe, Virginia.

At Fort Monroe, Butler made his most important contribution to the War effort, not in battle but through a clever legality. Overstepping his authority once again, he decreed that slaves who escaped to Union territory were not subject to the U.S. Fugitive Slave Law. The reasoning went, “upon the Confederate theory of [slaves being] property only,” if said property served military purposes, such as digging fortifications, then the Union could retain them as “contraband.” Butler’s “contraband” order laid the groundwork for Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. Thomas Morris Chester, Black news correspondent, was a fan of Butler and his logic.

Again exceeding his authority, Butler extended the protection of the Union to Black people, including women and children, who didn’t serve military objectives. “Of the humantiarian aspect I have no doubt,” he wrote Gen. Scott.

In 1864 he wrote to the Sec. of War: “I have not proposed to allow negroes to be taken from Fort Monroe, where they are free, into the slave state of Delaware, where they may be sold into slavery.” (Throughout the War, Delaware’s General Assembly resisted Federal efforts at emancipation; its slaves were not legally free until December 1865, after national passage of the 13th Amendment.)

When Pres. Lincoln’s administration moved to bar fugitive slaves from crossing Union lines, Butler declared that he would not enforce such a policy and further declared that the fugitives were not only “contraband,” but that they were free. “In a state of rebellion I would confiscate that which was used to oppose my arms,” he wrote the Sec. of War, “… and if, in so doing, it should be objected that human beings were brought to the free enjoyment of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, such objection might not require much consideration.”

Benjamin Butler approved what was likely the first instance of arming a Black man for the Union cause. He perceived the potential of escaped slaves to gather vital intelligence. In New Orleans, he enlisted the first African American troops — overstepping, again, his authority. He commanded several regiments of U.S. Colored Troops, and agitated, without success, that they receive treatment and compensation equal to whites’. He struck silver medals, at his own expense, for his USCT regiment that fought at Richmond.

After the War, as a radical Republican, he helped pass the Civil Rights Act of 1875 (which was overturned in 1883). He also supported women’s suffrage.

Butler wasn’t born a steadfast civil rights advocate. In his early career, he supported the Dred Scott ruling that African Americans had no rights. He voted for Jefferson Davis at the 1860 Democratic National Convention, for the sake of party unity.

The War changed Butler. Or rather, meeting fugitive slaves changed him. Seeing his Colored Troops in battle transformed him into an impassioned abolitionist. He wrote to his wife:

Poor fellows, they seem to have so little to fight for in this contest, with the weight of prejudice loaded upon them, their lives given to a country which has given them not yet justice, not to say fostering care. To us, there is patriotism, fame, love of country, pride, ambition, all to spur us on, but to the negro, none of all these for his guerdon of honor. But there is one boon they love to fight for, freedom for themselves and their race forever, and may my “right hand forget her cunning” but they shall have that. The man who says the negro will not fight is a coward, and his liver is white, and that is all there is truly white about him. His soul is blacker than the dead faces of these dead negroes, upturned to heaven in solemn protest against him and his prejudices. I have not been so much moved during this war as I was by this sight. Dead men and many of them I have seen, alas! too many, but no such touching sight as this.

Should a man who wrote such words go down in history as “ugly”?

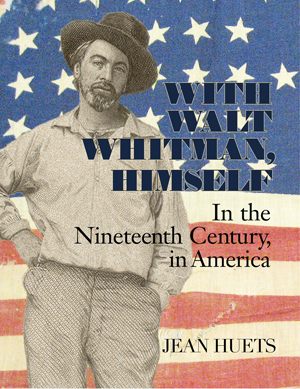

WITH WALT WHITMAN, HIMSELF: IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, IN AMERICA | by Jean Huets

“A true Whitmanian feast—for the intellect as well as for the eyes.” — Ed Folsom, editor Walt Whitman Quarterly

Amazon | B&N | bookshop.org (supports indie booksellers)

signed copies, free shipping order from Circling Rivers

“A beautiful book of windows onto the life of Walt Whitman…. From the clear ringing prose to the fascinating photographs and colored illustrations of the great poet’s life we find the man anew—standing in his time and looking straight at us. [Huets] has made a book of marvels and I can’t put it down.” — Steve Scafidi, Poet Laureate, Virginia

Explore the fascinating roots of Whitman’s great work, Leaves of Grass: a family harrowed by alcoholism and mental illness; the bloody Civil War; burgeoning, brawling Manhattan and Brooklyn; literary allies and rivals; and his beloved America, racked by disunion even while racing westward. Over 300 color period images immerse the reader in the life and times of Walt Whitman.

Private and Official Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin F. Butler….; Adam Goodheart, 1861: The Civil War Awakening; Douglas Harper, “Slavery in the North” via slavenorth.com; “Major-General Butler,” Harper’s Weekly, June 1, 1861, via sonofthesouth.net

Pingback:Most handsome Civil War general | Leaves of Grass

Pingback:Thomas Morris Chester & racism in the ranks | Leaves of Grass

Pingback:Most handsome Civil War general | JEAN HUETS