The meat of the United States Census, taken every ten years, is the body of statistics drawn up on the people questioned. Yet the questions themselves, and the manner of asking them, reveal (and conceal) the values of U.S. society, mutating every 10 years.

The 2020 Census, for example, drew controversy with the proposal to add the question: “Is this person a citizen of the United States?” The topic of citizenship has come and gone in various forms on the census. (The decision was not to include it in 2020.)

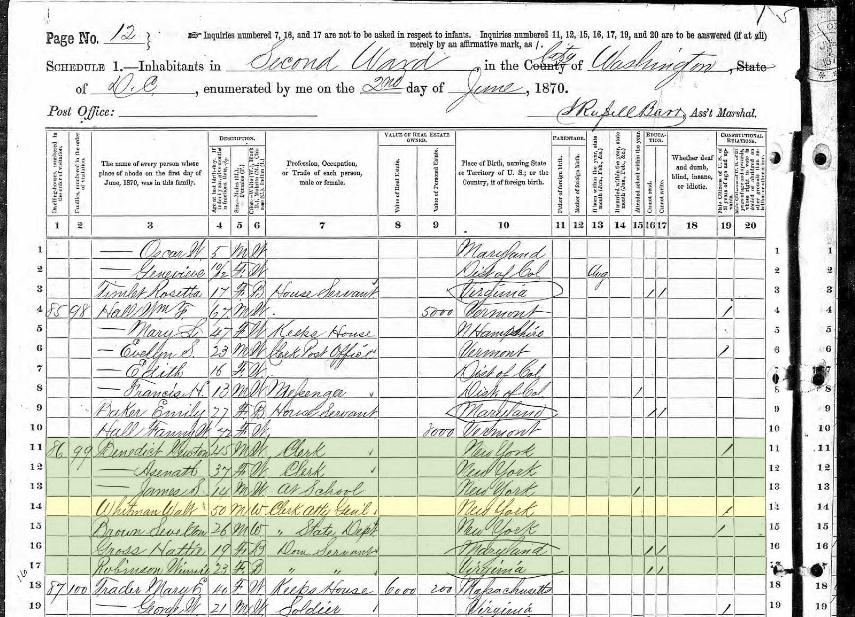

The 1870 Census, the first following the Civil War, is a fascinating document, in its questions and in the instructions for asking them.

By way of background, some conditions in 1870 United States:

- The continental shape of the United States was nearly identical to what it is today. All states that had seceded were back in the Union. The last, readmitted in 1870, were Virginia (January), Mississippi (February), Texas (March), and Georgia (July). The others had been readmitted in 1868.

- All states and territories were included in the 1870 United States Census. The “newly acquired district of Alaska” was not canvased, but population figures were “stated according to the best available data, consisting mainly of reports, nominal lists, &c., from officers of the Army on duty in that military department.” (3)

- The 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified on February 3, 1870, prohibited the federal government and each state from denying a male citizen the right to vote based on that citizen’s “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” (Women of any “race, color, or previous condition” did not receive equal protection of their right to vote until the 19th Amendment was passed on June 4, 1919.)

- Career military men, such as George Armstrong Custer and Philip H. Sheridan, who had been displaced by the end of the Civil War found renewed opportunities out West in the ongoing “Indian Wars.” (The Civil War offered the same kind of opportunity to displaced Mexican War officers.)

The 1870 Census

Assistant Marshals, as Census takers were called, received detailed instructions in the quest for detailed and accurate data. “Strict and literal compliance will be enforced,” they were admonished. The forms were filled out by hand in ink.

Following are the questions (in bold), with extracts from the instructions. The instructions, more than the questions themselves, are curious reflections of their time. For example, all Asians were considered “Chinese”; several occupations, eg, “paper-bonnet maker” and “apothecary’s apprentice” are now defunct. “Clerks” are no longer asked to sleep at their work premises “for purposes of security.”

1. Dwelling houses and number in order of visitation.

… Hotels, poor-houses, garrisons, asylums, jails, and similar establishments, where the inmates live habitually under a single roof, are to be regarded as single dwelling-houses for the purposes of the Census…. Eating-houses, Stores, Shops, &c. Very many persons, especially in cities, have no other place of abode than stores, shops, &c.; places which are not primarily intended for habitation. Careful inquiry will be made to include this class, and such buildings will be reckoned as Dwelling-houses within the intention of the Census law; but a watchman, or clerk belonging to a family resident in the same town or city, and sleeping in such store or shop merely for purposes of security, will be enumerated as of his family.

2. Families numbered in the order of visitation.

A single person, living alone in a distinct part of a house, may constitute a family; while, on the other hand, all the inmates of a boarding-house or a hotel will constitute but a single family, though there may be among them many husbands with wives and children. [Interesting use of the word “family”: people, whether related or not, living in the same building unit. Census is still done in this way; recorded by the building unit people live in.]

3. The name of every person whose place of abode on the 1st day of June, 1870, was in this family.

The name of the father, mother, or other ostensible head of the family (in the case of hotels, jails, &c., the landlord, jailor, &c.) is to be entered first of the family. The family name is to be written first in the column, and the full first, or characteristic christian or “given” name of each member of the family in order thereafter…. Sea-faring men are to be reported at their land homes, no matter how long they may have been absent, if they are supposed to be still alive. Hence, sailors temporarily at a sailors’ boarding or lodging house, if they acknowledge any other home within the United States, are not to be included in the family of the lodging or boarding house. Persons engaged in internal transportation, canal-men, express-men, railroad-men, &c., if they habitually return to their homes in the intervals of their occupation, will be reported as of their families, and not where they may be temporarily staying on the 1st of June.

DESCRIPTION:

4. Age at last birthday. If under 1 year, give months in fractions, thus, 3/12.

5. Sex – Males (M), females (F).

6. Color – White (W), black (B), mulatto (M), Chinese (C), Indian (I).

It must not be assumed that, where nothing is written in this column. “White” is to be understood. The column is always to be filled. Be particularly careful in reporting the class Mulatto. The word is here generic, and includes quadroons, octoroons, and all persons having any perceptible trace of African blood. Important scientific results depend upon the correct determination of this class.… [The nature of those “scientific results” is not given in the instructions.]

7. Profession, occupation, or trade of each person, male or female.

The inquiry “Profession, Occupation, or Trade,” is one of the most important questions of this schedule. Make a study of it. Take especial pains to avoid unmeaning terms, or such as are too general to convey a definite idea of the occupation. Call no man a ” factory hand” or a “mill operative.” State the kind of a mill or factory. The better form of expression would be, “works in cotton mill,” “works in paper mill,” &c. Do not call a man a “shoemaker,” “bootmaker,” unless he makes the entire boot or shoe in a small shop. If he works in (or for) a boot and shoe factory, say so.

Do not apply the word “jeweler” to those who make watches, watch chains, or jewelry in large manufacturing establishments. .

Call no man a “commissioner,” a “collector,” an “agent,” an “artist,” an “overseer,” a “professor,” a “treasurer,” a “contractor,” or a speculator,” without further explanation.

When boys are entered as apprentices, state the trade they are apprenticed to, as “apprenticed to carpenter,” “apothecary’s apprentice.”

When a lawyer, a merchant, a manufacturer, has retired from practice or business, say “retired lawyer,” “retired merchant,” &c. Distinguish between fire and life insurance agents.

When clerks are returned, describe them as “clerk in store,” ” clerk in woolen mill,” “R. R. clerk,” “bank clerk,” &c.

Describe no man as a “mechanic” if it is possible to describe him more accurately.

Distinguish between stone masons and brick masons.

Do not call a paper-bonnet maker a bonnet manufacturer, a lace maker a lace manufacturer, a chocolate maker a chocolate manufacturer. Reserve the term Manufacturer for proprietors of establishments: always give the branch of manufacture.

Whenever merchants or traders can be reported under a single word. expressive of their special line, as “grocer,” it should be done. Otherwise, say dry goods merchant, coal dealer, &c.

Add, in all cases, the class of business, as wholesale (wh.), retail (ret.), importer (imp.), jobber, &c.

Use the word Huckster in all cases where it applies.

Be very particular to distinguish between farmers and farm laborers. In agricultural regions this should be one of the point to which the Assistant Marshal should especially direct his attention.

Confine the use of the words “glover,” “hatter,” and “furrier” to those who actually make, or make up, in their own establishments, all, or a part, of the gloves and hats or furs which they sell. Those who only sell these articles should be characterized as “glove dealer,” “hat and cap dealer,” “fur dealer.”

Judges (state whether federal or State, whether probate, police, or otherwise) may be assumed to be lawyers, and that addition, therefore, need not be given; but all other officials should have their profession designated, if they have any,’ as “retired merchant, governor of Massachusetts,” “paper manufacturer, representative in legislature.” If anything is to be omitted, leave out the office, and put in the occupation.

As far as possible distinguish machinists as “locomotive builders,” “engine builders,” &c.

Instead of saying “packers,” indicate whether you mean “pork packers” or “crockery packers,” or “mule packers.”

The organization of domestic service has not proceeded so far in this country as to render it worth while to make distinction in the character of work. Report all as “domestic servants.”

Cooks, waiters, &c., in hotels and restaurants will be reported separately from domestic servants.

The term “house-keeper” will be reserved for such persons as receive distinct wages or salary for the service. Women keeping house for their own families or for themselves, without any other gainful occupation, will be entered as “keeping house.” Grown daughters assisting them will be reported without occupation.

You are under no obligation to give any man’s occupation just as he expresses it. If he cannot tell intelligibly what he is, find out what he does, and characterize his profession accordingly.

The inquiry as to Occupation will not be asked in respect to infants or children too young to take any part in production. Neither will the doing of domestic errands or family chores out of school be considered an occupation. “At home” or “attending school” will be the best entry in the majority of cases. But if a boy or girl, whatever the age, is earning money regularly by labor, contributing to the family support, or appreciably assisting in mechanical or agricultural industry, the occupation should be stated.

VALUE OF REAL ESTATE OWNED

8. Value of real estate.

Property, column 8 will contain the value of all Real Estate owned by the. person enumerated, without any deduction on account of mortgage or other incumbrance, whether within or without the Census subdivision or the county. The value meant is the full market value, known or estimated.

9. Value of personal estate.

Personal Estate, column 9, is to be inclusive of all bonds, stocks, mortgages, notes, live stock, plate, jewels, or furniture; but exclusive of wearing appareL No report will be made when the personal property is under one hundred dollars.

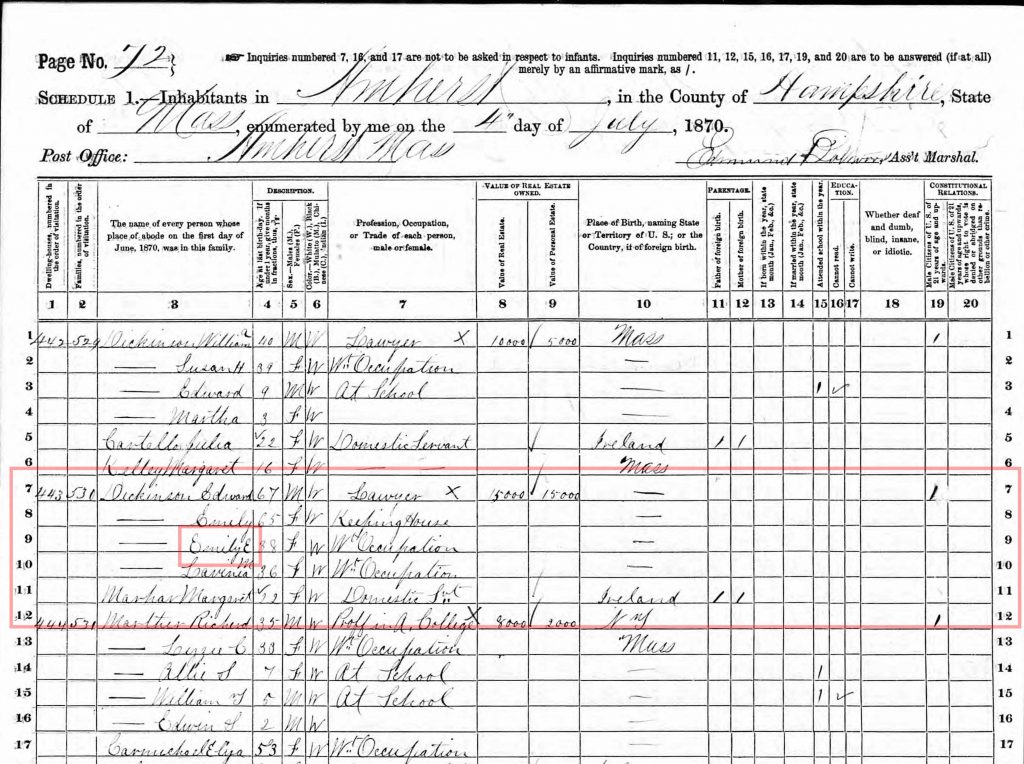

[The value of Edward Dickinson’s real estate brings home the wealth gap: lawyer Dickinson’s “value” in Amherst, Massachusetts was $15,000 / $15,000, whereas the “value” held by a farmer (related to one of my ancestors) in Sanford County, Alabama was $200 / $400.]

10. Place of birth, naming the state or territory of the United States, or the country, if of foreign birth.

Column 10 will contain the “Place of Birth” of every person named upon the schedule. If born within the United States, the State or Territory will be named, whether it be the State or Territory in which the person is at present residing or not. If of Foreign birth, the Country will be named as specifically as possible. Instead of writing “Great Britain” as the place of birth, give the particular country, as England, Scotland, Wales. Instead of “Germany,” specify the State, as Prussia, Baden, Bavaria, Wurtemburg, Hesse Darmstadt, &c.

PARENTAGE:

11. Father of foreign birth.

[Answered yes, with a slash, or no, with no mark. This is how I found out that an early 18th-century ancestor was born in Germany, not in North Carolina as we’d thought.]

12. Mother of foreign birth.

[Answered yes, with a slash, or no, with no mark.]

13. If born within the year, state month (Jan., Feb., etc.).

14. If married within the year, state month (Jan., Feb., etc.).

EDUCATION:

15. Attended school within the year.

16. Can not read.

17. Can not write.

It will not do to assume that, because a person can read, he can, therefore, write. The inquiries contained in columns 16 and 17 must be made separately. Very many persons who will claim to be able to read, though they really do so in the most defective manner, will frankly admit that they cannot write. These inquiries will not be asked of children under ten years of age. In regard to all persons above that age, children or adults, male and female, the infirmation will be obtained.

18. Whether deaf and dumb, blind, insane, or idiotic.

Great care will be taken in performing this work of the enumeration, so as at once to secure completeness and avoid giving offense. Total blindness and undoubted insanity only are intended in this inquiry. Deafness merely, without loss of speech, is not to be reported. The fact of idiocy will be better determined by the common consent of the neighborhood, than by attempting to apply any scientific measure to the weakness of the mind or will.

CONSTITUTIONAL RELATIONS:

19. Male citizens of United States of 21 years of age and upwards.

Upon the answers to the questions under this head will depend the distribution of representative power in the General Government. It is therefore imperative that this part of the enumeration should be performed with absolute accuracy. Every male person born within the United States, who has attained the age of twenty-one years, is a citizen of the United States by the force of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution; also, all persons born out of the limits and jurisdiction of the United States, whose fathers at the time of their birth were citizens of the United States (act of February 10, 1855); also, all persons born out of the limits and jurisdiction of the United States, who have been declared by judgment of Court to have been duly Naturalized, having taken out both “papers.”

20. Male citizens of United States of 21 years of age and upwards, whose right to vote is denied or abridged on other grounds than rebellion or other crime.

The part of the enumerator’s duty which relates to column 19 is therefore easy, but it is none the less of importance. It is a matter of more delicacy to obtain the information required by column 20. Many persons never try to vote, and therefore do not know whether their right to vote is or is not abridged. It is not only those whose votes have actually been challenged, and refused. at the polls for some disability or want of qualification, who must be reported in this column; but all who come within the scope of any State law denying or abridging suffrage to any class or individual on any other ground than participation in rebellion, or legal conviction of crime. Assistant Marshals, therefore, will be required carefully to study the laws of their own States in these respects, and to satisfy themselves, ill the case of each male citizen of the United. States above the age of twenty-one years, whether he does or does not come within one of these classes.

As the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, prohibiting the exclusion from the suffrage of any person on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, has become the law of the land, all State laws working such exclusion have ceased to be of virtue. If any person is, in any State, still practically denied the right to vote by reason of any such State laws not repealed, that denial is merely an act of violence, of which the courts may have cognizance, but which does not come within the view of Marshals and their Assistants in respect to the Census.

WITH WALT WHITMAN, HIMSELF: IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, IN AMERICA | by Jean Huets

“A true Whitmanian feast—for the intellect as well as for the eyes.” — Ed Folsom, editor Walt Whitman Quarterly

Amazon | B&N | bookshop.org (supports indie booksellers)

signed copies, free shipping order from Circling Rivers

“A beautiful book of windows onto the life of Walt Whitman…. From the clear ringing prose to the fascinating photographs and colored illustrations of the great poet’s life we find the man anew—standing in his time and looking straight at us. [Huets] has made a book of marvels and I can’t put it down.” — Steve Scafidi, Poet Laureate, Virginia

Explore the fascinating roots of Whitman’s great work, Leaves of Grass: a family harrowed by alcoholism and mental illness; the bloody Civil War; burgeoning, brawling Manhattan and Brooklyn; literary allies and rivals; and his beloved America, racked by disunion even while racing westward. Over 300 color period images immerse the reader in the life and times of Walt Whitman.

Sources: 1. Questions | 2. Instructions | 3. Compendium of the Ninth Census [1870] | Margaret Maher

Pingback:Broken Bands and Scattered Remnants: Native Americans in 1870 USA | JEAN HUETS