A line in Walt Whitman’s poem (today known as) “I Sing the Body Electric” appeared only in the first (untitled) 1855 edition:

Framers bare-armed framing a house . . hoisting the beams in their places . . or using the mallet and mortising-chisel

Until the mid-19th century, houses had no framework at all, as in a log cabin, or they were timber framed (post-and-beam construction).

The “skeleton” or frame of a timber-framed house has vertical beams, or posts, usually only at the corners, and horizontal beams, or girts. Each post and girt runs the height or length of an entire section of the house and therefore has to be massive enough to support walls, floors, contents, and roof. During Walt’s youth, such timber became hard to find as people, industry, and railroads devoured trees for fuel and building.

Nails would pull out under the load of post-and-beam construction, so mortise-and-tenon joints held together posts and girts. The mortise (a slot or square / rectangular hole in the timber) and the tenon (a protrusion to fit into the mortise) were made “using the mallet and mortising chisel.” The joinery demanded the skill of a master carpenter, for mortise and tenon had to fit snugly to ensure the stability of the house.

Balloon framing, an 1830s innovation from Chicago, rapidly superceded timber framing as being cheaper, easier, and faster. A balloon frame uses multiple smaller timbers to support the building. (To an unschooled eye, a balloon frame looks pretty much the same as today’s platform frame (stud-and-deck construction). Because the load is distributed, ballon frames do not depend on massive timbers, and the studs (vertical) and joists (horizontal) can be nailed together rather than joined. The process lent itself to a more “assembly-line” labor dynamic with fewer skilled workers needed. Materials were cheaper, since studs and joists could be milled offsite to uniform dimensions for any number of buildings, and nails were no longer hand-wrought but “cut” by machine.

“There are certain characteristics of balloon-frame construction that are a giveaway, a tattle-tale if you will, from the outside that should alert us to the presence of balloon-frame construction. Things such as window and door openings from first to second floor, all lining up vertically. Tall wall heights for two-story structures are fairly common. Also what looks to be a very old appearance with clapboard siding and usually roof rafters that are in some cases exposed and appear to be much smaller dimensional material than later conventional construction.” The wall heights can be contrasted with the markedly low ceilings typical of many timber framed dwellings.

Walt Whitman’s father, a master carpenter, moved his family from Huntington, Long Island to Brooklyn in 1823. He hoped to profit from the housing boom there, but he never established himself comfortably. Balloon framing hadn’t yet taken hold when the family moved back to Long Island in 1833. National financial downturns and a personal lack of business acumen defeated Walter Whitman, Sr.. By 1855, though, when the first edition of Leaves of Grass came out, balloon framing had made obsolete Walter Whitman’s artisanal methods.

The old-time timber framers had another home, though, in “Song of Myself”:

Accepting the rough deific sketches to fill out bet-

ter in myself—bestowing them freely on

each man and woman I see,

Discovering as much, or more, in a framer framing

a house,

Putting higher claims for him there with his

rolled-up sleeves, driving the mallet and

chisel,

The deification of the framers had a personal and poignant meaning to Walt. Walter Whitman died, ending a long decline, on July 11, 1855, only about a week after the first edition of Leaves of Grass was issued. On Whitman’s question: Where is your father?

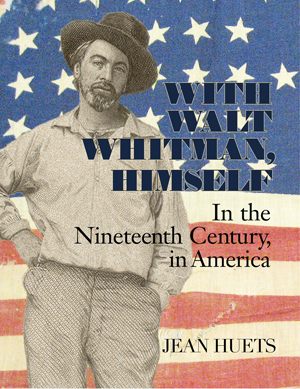

WITH WALT WHITMAN, HIMSELF: IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, IN AMERICA | by Jean Huets

“A true Whitmanian feast—for the intellect as well as for the eyes.” — Ed Folsom, editor Walt Whitman Quarterly

Amazon | B&N | bookshop.org (supports indie booksellers)

signed copies, free shipping order from Circling Rivers

“A beautiful book of windows onto the life of Walt Whitman…. From the clear ringing prose to the fascinating photographs and colored illustrations of the great poet’s life we find the man anew—standing in his time and looking straight at us. [Huets] has made a book of marvels and I can’t put it down.” — Steve Scafidi, Poet Laureate, Virginia

Explore the fascinating roots of Whitman’s great work, Leaves of Grass: a family harrowed by alcoholism and mental illness; the bloody Civil War; burgeoning, brawling Manhattan and Brooklyn; literary allies and rivals; and his beloved America, racked by disunion even while racing westward. Over 300 color period images immerse the reader in the life and times of Walt Whitman.

SOURCES: Francis D.K. Ching, Building Construction Illustrated; quote on balloon frame characteristics; Long Beach Fire Department; Photo by William Henry Jackson, Collection National Building Museum.

“Whitman

Nice post on the balloon frame of houses. Houtskeletbouw (timber frame) homes have evolved in multiple folds to reach to heights of innovation. I recently built a timber frame home in Belgium. Although we had some constraints with respect to the floor space, the builders have done a good job in its design frame. We opted for a slated type of roof and the final results have come out very promising.

Thanks for stopping by! I’m glad to see artisan building happening today.