On April 30, 1871, the Camp Grant massacre took place.

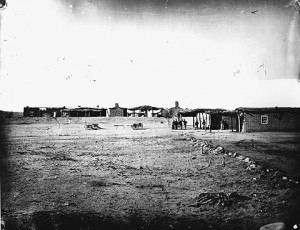

Tensions had been rising between the Apache Indians and American settlers. But the commander of Camp Grant, Lt. Royal Emerson Whitman, had recently negotiated peace with a group of Apaches. With the Apaches “pacified”, Whitman and the US Army became responsible for feeding and protecting them, and all boded well for an easing of tensions. But ongoing depredations, charged to the Camp Grant Indians, endangered the fragile new status quote.

Lt. Whitman’s attempts to mediate the tensions between settlers and Indians received little support from General George Stoneman, who had famously raided North Carolina and southern Virginia during the Civil War, and now commanded Arizona Territory. The settlers despised Stoneman for brushing problematic “Indian affairs” under the carpet and for recommending closure of several military bases. William Belknap, President Grant’s Secretary of War, was no doubt distracted by the lucrative business of impoverishing US soldiers through the sale of trading monopolies on the Western frontier.

A posse of American and Papago (O’odham) locals decided to take matters into their own hands.

On the morning of April 30, Lt. Whitman received warning that “a large party” had left Tuscon to raid the camp. By the time he arrived, “their camp was burning, and the ground strewn with their mutilated women and children.” Of the 144 Apaches killed, only 8 were men. Over two dozen captured children were sold into slavery in Mexico.

Lt. Whitman’s official report, a “fearful tale” of “women and children butchered,” was excerpted in the New York Times and other Eastern papers. Faced with public outrage, President Grant threatened to put the Arizona Territory under military rule unless the perpetrators were brought to justice.

A grand jury duly indicted a posse including “five white men and twenty Mexicans whose names we knew, and seventy-five Papagos by fictitious names.” (American Latinos are usually labeled Mexicans in the documents.)

In less than 20 minutes, every single man was acquitted. Territorial Governor Safford, whose adjutant general furnished “a wagonload of arms and ammunition for the Papago Indians” to carry out the massacre, kept on governing. A few other men involved were later elected to U.S. Congress. Lt. Whitman’s scathing report and his sympathy for the Indians earned him a court martial on charges of drunkenness, trumped up by Safford. (Whitman was acquitted, once he’d been out of the way long enough.)

Evidently satisfied that justice had been served, President Grant let the matter go.

Sources: Arizona’s Camp Grant Massacre, by Howard Sheldon / Grand jury – “The Camp Grant Massacre,” by Andrew H. Cargill. Arizona historical review 7, no 3 July 1936. Reprinted in Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865-1890: The Struggle for Apacheria, by Peter Cozzens, pp. 63-67 / “The Camp Grant Massacre” extracted from Lt. Whitman’s official report dated May 17, 1871, and printed in the New York Times, July 19, 1871 (available in the NYT archives)

Pingback:Apaches versus Arizona Territory