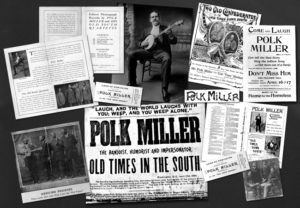

This is part 5 of the story (in 5 parts, plus one digression) of a white man who tried to glue together his life, sliced in two by the Civil War, by uniting in himself the most irretrievable parts of his past: master and slave. It’s a story that cobbles together, too, a paradox of American music — a paradox of music anywhere: that the exploitation of folk music by privilege is often the essence of its preservation. It’s the story of Polk Miller, “Negro delineator.”

POLK MILLER: 1 Roots | 2 “Old Plantation Negro” | 3 “Young Negroes” | 4 Rising Controversy | 5 Appropriation & Preservation | Cats & Dogs

Before hardening racial tension destroyed the uneasy “separation by consent” status quo, Polk Miller’s stage act benefited from it. “‘Separation by consent’ — where and while it survived — made performances by blacks and whites on the same stage acceptable: everyone knew “their place.” Outside of the Old Dominion, this convention was less known. “Separation,” from Chicago to Birmingham, had to be marked by a clear, uncrossable line. After 1912, Miller never toured again.

The sheet music to Miller’s own songs, such as “I’m goin’ to Ole Virginny,” continued to achieve good sales nationally, as did recordings of the Quartette. “Naturally the demand was greatest in the South,” said the March 1910 Edison Phonograph Monthly, “still the North took to them very kindly and some sections of the West simply cannot get enough of them.… The popularity of the records proves that real ‘darkey’ plantation melody still has a firm grip upon the affections of the American public, irrespective of locality.”

Polk Miller died in October 1913, just shy of 70 years old. Over a century later, Sergeant’s Pet Care Products continues enshrine his favorite old dog and guard the comfort of our animal companions.

Recordings of the Old South Quartette are available as CDs and MP3s and on youtube, but the ugly shadow of racism threatens to blot out Polk Miller’s musical legacy. Miller propogated damaging stereotypes both of slavery and the enslaved. Music historians Dick Spottswood and Tim Brooks prefer to “separate [Miller’s] music from the social beliefs he espoused.” Says Brooks, “He was preserving what this culture of black America was really like and what it sounded like in the 1840s and 1850s, and no one else was doing that.”

Can an apologist for slavery be praised for helping maintain the oral traditions and folk music of a people, time and place that was passing from living memory? Is it okay to laugh along with the jovial vocals of “Oysters and Wine at 2 a.m.”? It requires compromise, and compromise is awfully hard to muster, in American race relations.

Miller, as a Civil War era white man and a “Negro delineator,” presents a case study of what psychologists term cognitive dissonance, the stress that arises from clinging to contradictory or paradoxical values. Miller loved African American heritage, dedicating himself to the banjo and lapsing into dialect even in personal letters, as if it were his true tongue. The music and conversation of the slaves on his father’s farm deeply imprinted him, glowing in the light of life as a privileged child. So, too, did the conviction that the best life for African Americans was an eternal childhood watched over by a benevolent white ruling class. Boyhood ties of affection with enslaved women, men and children never matured into an embrace of racial equality or allowed him to grasp the urgent need of African Americans, and whites as well, to break free of slavery.

In 1956, a little over 100 years after Miller’s birth, his birthplace Prince Edward County became ground zero for “Massive Resistance,” a movement against desegregation that closed public schools for five years. State-funded “tuition grants” subsidized “segregation academies” for white children. The descendants of Polk Miller’s enslaved childhood friends relied for their education on volunteers, black and white, many from far away.

To a degree unmatched by their fellow citizens up north, white and black Southerners faced an unbridgeable divide between antebellum and postbellum life, slavery and Emancipation. Many on both sides of the color line gladly settled on the postbellum side. Not so Miller. Despite financial success, social prominence, devoted friends, and a tranquil domestic life, the Civil War and Emancipation left Miller stranded in “ole Virginny.” But this place and time no longer existed, if it ever did. Miller’s beloved “Southern negro” turned out to be the “aspiring negro,” and the “many negro boys” who rambled with him and his brothers through the glowing land of childhood simply wouldn’t stay by his side.

Sources: Jas Obrecht, “Polk Miller and His Old South Quartette.” via jasobrecht.com. Obrecht’s website includes links to Polk’s recordings, along with illuminating commentary and quotes from Edison Phonograph’s promotional materials.