Walt Whitman gives beauty to the soldiers dying under his care in the hospital. The goriest, most wrenching passage in his Memoranda During the War is for the dead on the field: “Slaughterhouse!—O well it is their mothers, their sisters cannot see them—cannot conceive, and never conceiv’d, these things.” He continues with the horrors of the body parts strewn, the chalk-white face, the bowel shot.

Read my article “The Union Dead” in New York Times Disunion.

Frank Wilkeson’s Civil War memoir also opts for brutal honesty. In the chapter devoted to battlefield death he debunks his comrades’ reports of friends’ dead faces “wreathed in smiles”:

I do not believe that the face of a dead soldier, lying on a battle-field, ever truthfully indicates the mental or physical anguish, or peacefulness of mind, which he suffered or enjoyed before his death. The face is plastic after death, and as the facial muscles cool and contract, they draw the face into many shapes. Sometimes the dead smile, again they stare with glassy eyes, and lolling tongues, and dreadfully distorted visages at you. It goes for nothing. One death was as painless as the other.

Ambrose Bierce writes of Shiloh’s dead: “The contraction of muscles which had given them claws for hands had cursed each countenance with a hideous grin. Faugh! I cannot catalogue the charms of these gallant gentlemen who had got what they enlisted for.” This description, though, isn’t bluntly honest, as Bierce’s personal bitterness evokes sarcasm and emotionally loaded words such as “cursed” and “hideous.”

click to Tweet: #USCivilWar Dead, for real. @JeanHuets http://ctt.ec/8k6bK+

The dead soldiers on Civil War battlefields, as photographed, mostly wear neutral expressions. The eyes may be open, but they’re just blank, not “staring” as the usual description has it. The mouths don’t necessarily gape, though they tend to be open. The cheeks look a bit sunken, but not as much as one might expect. The aspect of the bodies, if photographed as they fell, merely reflect where death came from: if from the front, the bodies lie on their backs, face to sky, often with arms flung overhead. If from above, as with artillery, the body can end up in any position: curled on the side, prone, or supine. (No photos here, but you can go to the Library of Congress Collection of images, search “dead” and see for yourself.)

The photos aren’t repulsive. But they are of men, humans, and hence profoundly sad. The cumulative effect of viewing them is of melancholy and dreary horror.

Letters sent home during the Civil War tried to paint a gracious picture of a comrade’s death, something to comfort loved ones. But the “expression” on a dead person’s face doesn’t display the state of mind at death, or the kind of death suffered, violent or peaceful. It reflects only the ultimate physical process: death’s grip. Comfort can’t be found in the myth of the beautiful corpse.

Religious people have an alternative at hand, with dreams of salvation and heaven. Others may be inspired by the possibility Walt Whitman presents, that we live eternally in others and in the earth, even if we are forced to abandon the form to which we are so attached. And the leap of faith: whatever the circumstances, passing into death is passing into the unknown, and “luckier” than we can guess.

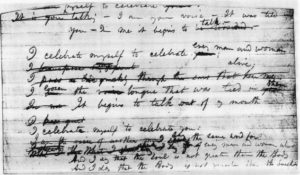

What do you think has become of the young and old men?

And what do you think has become of the women and chil-

dren?They are alive and well somewhere,

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death,

And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the

end to arrest it,

And ceas’d the moment life appear’d.All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses,

And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.

Sources: Library of Congress. Faust, Drew Gilpin. The Republic of Suffering. Whitman, Walt. “Song of Myself.” Drafts: Collection of University of Iowa. Wilkeson, Frank. Turned Inside Out: Recollections of a Private Soldier in the Army of the Potomac.