This is part 2 of the story (in 5 parts) of a white man who tried to glue together his life, sliced in two by the Civil War, by uniting in himself the most irretrievable parts of his past: master and slave. It’s a story that cobbles together, too, a paradox of American music — a paradox of music anywhere: the exploitation of folk music by privilege is often the essence of its preservation. It’s the story of Polk Miller, “Negro delineator.”

This is part 2 of the story (in 5 parts) of a white man who tried to glue together his life, sliced in two by the Civil War, by uniting in himself the most irretrievable parts of his past: master and slave. It’s a story that cobbles together, too, a paradox of American music — a paradox of music anywhere: the exploitation of folk music by privilege is often the essence of its preservation. It’s the story of Polk Miller, “Negro delineator.”

POLK MILLER: 1 Roots | 2 “Old Plantation Negro” | 3 “Young Negroes” | 4 Rising Controversy | 5 Appropriation & Preservation | Cats & Dogs

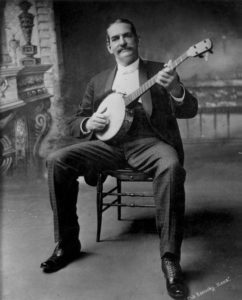

Two circumstances eased Polk Miller into living his dream of devoting himself to African American roots music. One was semi-retirement from pharmacy business in 1892, at age 47. The other was exactly what Miller longed for: African American music roared into fashion. Miller not only played his banjo openly, he played it on stage. Success came swiftly. A Baltimore impresario wrote, praising his reputation as a banjo player and asking him to raise a quartet of “Southern singers for plantation and jubilee songs.” What delighted Miller more than the praise was the impresario’s assumption that Miller himself was black. For him, it was an endorsement of authenticity.

Miller considered himself an educator, what we might call a living historian or folklorist. Nearly a generation after Emancipation, he did his utmost to enact what was to him a vivid and truthful portrait of the “Old Virginia Plantation Negro,” as one of his shows was billed, telling stories in dialect and singing songs he’d heard in his youth.

Miller’s earliest stage appearances benefited Confederate memorials and “camps,” which housed elderly Confederate veterans. An 1892 “Confederate War Scenes” benefit for the Lee Camp (located in Richmond at the present-day campus of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts), offered a mix of songs, skits, and re-enactments: “Regiment passes by. Richmond ladies present the regiment with a beautiful Confederate flag.” “Polk Miller’s famous troupe” presented a “war scene” in which “all the darkies from the camp congregate and have a regular old Virginia plantation time of it.” Miller and his troupe, which included some of his brothers, appeared as “burnt cork artists.”

Miller soon washed off the black-face and appeared as himself in evening clothes, trusting his dramatic skills to convince audiences of the authenticity of his “Ole Plantation Negro.” His “Old Times in the South” tour included performances at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Nearly thirty years on from the War, Miller saw at the Fair “the best collection of portraits of Confederate Generals I have ever seen,” housed in a reconstruction of Libby Prison, “as natural to me as it was when it stood on Cary Street in Richmond.” The only sight “calculated to stir up the blood of a southern man,” was a Leslie’s Illustrated cartoon showing Jeff Davis in women’s clothes, supposedly donned by the Confederate president to avoid capture by Federal authorities.

At the Fair and elsewhere, Miller got rave reviews. A Wilmington, Delaware paper gives a typical report: “The stories illustrated the affectionate relations between the blacks and the whites who belonged to the old plantation families, in a pretty, truthful, often touchingly pathetic way.” In a Kentucky paper: “[Miller’s] happy faculty and thorough knowledge of the Virginia negro make him an inimitable delineator of the thought and language of that race, without detracting from his own charming personality.”

Mark Twain, himself an aficionado of dialect white and black, introduced Miller at Madison Square Garden, New York: “Mr. Miller is thoroughly competent to entertain you with his sketches, and I not only commend him to your intelligent notice, but personally indorse [sic] him. The stories I have heard him tell are the best I have heard.” The Massachusetts Springfield Union said, “It was pleasant indeed to see the institution [of slavery] in a light so favorable and inviting.”

The New England reviewer intended not the least bit of irony; the irony of the review is that it pinpoints, obversely, the rising controversy around the impersonation of slaves by white people. Dissent, for Miller, first spoke out in August 1895, when he performed at the Chautauqua Assembly of New York, a network of adult education programs independent of academia. One of Miller’s earliest performances had been for his local Chautaqua chapter.

A dispatch from the New York performance to a Virginia paper gives the impression that all went well: “Mr. Miller’s pictures of negro life and manners in the old times before the war was listened to by the highly cultured Northern audience that faced him for an hour and a half, the audience calling for him to go on and the management extending his time for half an hour.” The emphasis on the distinguished class of spectators, in a puff piece likely authored by Miller himself, was a defensive response to the less enthusiastic reception from black members of the “highly cultured Northern audience.”

Four African-American educators sent a message to the management of the Assembly, “His picture was not that of the aspiring negro of the South…. We feel that a great injustice has been done those negroes … in having only that grotesque and illiterate side of the negro presented, and by one who is not his friend, and who is responsible for the sad and deplorable state of affairs which he depicted.”

To keep his act alive, Miller would have to adjust it. 3 “Young Negroes”

sources: Polk Miller’s scrapbooks and memorabilia. Collection of Valentine Richmond History Center. | Program for Confederate War Scenes, December 6, 1892. | Polk Miller, “Polk Miller’s Views,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, September 1893. | Anonymous, “Amusements,” Wilmington Evening Journal, December 5, 1893. | Anonymous, “Polk Miller,” Louisville Critic, May 1895. | Anonymous, “Twain and Polk Miller,” Cincinnatti Commercial Gazette, 1895. | Anonymous, “Delighted His Audience,” Springfield Union, February 24, 1897. | H.G.M., “Polk Miller’s Hit,” Norfolk Virginian, August 17, 1895. | Anonymous, “The Aspiring Negro,” Richmond Dispatch, August 21, 1895.

Pingback:Polk Miller and "the young negroes"

Pingback:Polk Miller, roots