This is part 3 of the story (in 5 parts, with one slight digression) of a white man who tried to glue together his life, sliced in two by the Civil War, by uniting in himself the most irretrievable parts of his past: master and slave. It’s a story that cobbles together, too, a paradox of American music — a paradox of music anywhere: that the exploitation of folk music by privilege is often the essence of its preservation. It’s the story of Polk Miller, “Negro delineator.”

POLK MILLER: 1 Roots | 2 “Old Plantation Negro” | 3 “Young Negroes” | 4 Rising Controversy | 5 Appropriation & Preservation | Cats & Dogs

Polk was wounded when four African-American educators charged that his act presented “only that grotesque and illiterate side of the negro.” Miller did not see his act as grotesque in any way. He announced to the Chautauqua audience the following night: “I want it distinctly understood that in my talks I have no reference to the young negroes of to-day. I do not pretend to know anything of them.… ‘Poor white trash’ (that’s what all the young ones think we are) and the educated negroes will never mix, but the old-time darky and the southern white, old and young, are good friends and will live in peace and harmony.” The “great audience of representative northern people” applauded the statement.

Miller spoke the honest truth in saying he knew nothing of the “young negroes” of 1895. The descendants of emancipated men and women had no interest in enshrining their ancestors’ servitude to slave holders.

A white “Virginian,” as signed in an 1895 letter to the Richmond Dispatch, also objected to “so-called dialect readings.” A hand-written note on the clipping in Miller’s scrapbook identifies the author of the letter as Lewis H. Blair, “an atheist.” Blair was a Confederate veteran from a socially prominent, formerly slave-holding Richmond family. Like Miller, he described black people as “my playmates in boyhood, and servants and friends in later years.” Unlike Miller, he believed that “dialect readers and writers” held African Americans “up to the ridicule and derision of the world.” He continued, “It is incomprehensible to me why any Southern man would wish to revive and perpetuate the memories of negro slavery.”

Blair’s indignation, and that of the black audience members at Chatauqua, didn’t object to Miller’s performance of black roots music. What aroused anger was the idealization of slavery and the portrayal of black people as ignorant (though wily) buffoons.

Richmond’s African-American paper Southern News wrote, “Mr. Miller is very wrong when he says that the poor Negro has been brought from a state of perfect happiness and contentment into one in which, the battle of life has to be fought, etc. [The News was quoting a letter by Miller published in the Richmond Dispatch.] When did slavery ever produce happiness? When did the barter and sale of human beings produce contentment? Is it possible that the gentleman is hankering after those dark and bloody days when the overseer’s whip was wet with blood and the clank of the slave dealer’s chains could be heard?”

Polk Miller did not hanker after such cruel days. For him, they never existed. The mix of privilege and childhood naiveté made Miller’s “Southland” of slavery times “the Garden of Eden for white man and black man alike.” He asserted, “Go where you will among people raised in the South before the war, and men will tell you the best, the dearest, and the truest friends they ever had were the colored boys with whom they played on the old farm.”

Miller’s affection was sincere, but his defensive view on slavery was formed by a baleful trend pointed out by Blair’s 1895 letter. “It is only in the last fifty years” — note that Miller was born in 1844 — “that, forced by the necessities and exigencies of the situation, we began to look upon [slavery] as elevating and refining in its influences upon society, and considered it our duty to praise and defend it.”

Undaunted, Miller sought deeper authenticity by adding African American male vocalists to his act. In doing so, he unknowingly sabotaged his touring career.

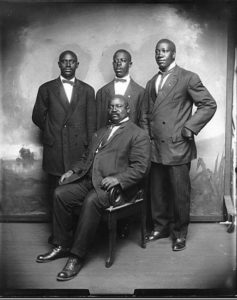

Polk Miller’s Old South Quartette, four African American male vocalists, was formed, as Miller put it, not from “the students from ‘colored universities,’ who dress in pigeon-tailed coats, patent leather shoes, white shirt fronts.” Miller recruited authenticity with performers who had been “singing on the street corners and in the barrooms of this city at night to motley crowds of hoodlums and barroom loafers and handing around the hat…. I could get a dozen quartettes from the good singing material among the Negroes in the tobacco factories here.” On recordings, Miller sang lead while the quartet sang backup. In performance for black audiences, the quartet apparently sang without Miller.

Extracted from Miller’s plantation life schtick, the Quartette drew praise from the African-American press for a mix of “plantation melodies and up to date songs.” The African-American newspaper Richmond Planet reported, “The old time melodies awakened memories of the past and caused an enthusiastic outburst of applause, as those who had listened clamored for more of the same kind.” “Old time” songs ranged from light-hearted — “The Watermelon Party” — to spiritual — “Jerusalem Mournin’”.

Given that the Planet review is dated 1909, more than forty years after Emancipation, plantation melodies would have struck a nostalgic chord only with the passing generation of formerly enslaved African Americans, the black people with whom Miller felt most comfortable. Songs such as “Pussy Cat Rag” appealed to younger audience members more tuned in to the burgeoning jazz movement.

Sources: Polk Miller’s scrapbooks and memorabilia. Collection of Valentine Richmond History Center | Lewis H Blair, “The Influence of Slavery upon the Negro,” Richmond Times, August 27, 1895. Blair expressed his convictions at more length in his 1888 book Unwise Laws. “I believe in the civil equality of every man, regardless of race or previous condition, and that every man should have a voice in the government under which he lives, and which, when called upon he must defend at the hazard of his life. I believe that laws should bear equally upon all, and that there should be no favoritism or discrimination against the negro because he is a negro.” (Quoted in Tyler, Lyon Gardiner. “Lewis H. Blair,” Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography. NY, 1915.) | Jacques Vest, “Polk Miller’s Old South Quartette,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol 120, no. 2, 147. | Anonymous, “The ‘Old Issue Darkey,’” Morning News, December 6, 1893.

Pingback:Polk Miller: Rising Controversy

Pingback:Polk Miller: "Old Plantation Negro"