Early tarot cards — used for gaming, not divination — emblemize the midpoint of fifteenth-century Italy, a crossroads of Medieval imagination and Renaissance intellect. They may have been inspired by Petrarch’s circa 1374 The Triumphs. The poem is modeled on ancient Roman triumphal parades, but rather than celebrating conquerors, it celebrates virtues that successively “triumph” over one another: Chastity, for example, triumphs over Love, and Death trumps both.

Lombardy, December 1450: Francesco Sforza, the duke of Milan, orders “carte de triumphi, della più belle poray trovare,” “triumph cards, of the most beautiful that can be found.”

Francesco’s triumph cards are called tarot today. His order is one of the earliest historical references to tarot, and the hand-painted cards attributed to his court artist Bonifacio Bembo are among the earliest extant tarot decks. On The Early Tarot Artists at Work

Poetic as the allegorical cards were, and although tarot is now used by occultists and fortunetellers, Francesco’s beautiful triumphi were used primarily for a trick-taking game—and for showing off.

Francesco Sforza and Bianca Maria Visconti are celebrating their first Advent as ducal couple in grand style. The triumph deck is but one of the amusements. Their guests gather at a knee-high card table of thick, dark, carved wood.

Renaissance fashion has not arrived in conservative Milan. Not yet, the low-necked, tailored dresses with laced bodices and sleeves. The ladies still wear houpelandes, full-cut garments of wool and silk damask (milled in Lombardy) over colorful underdresses. Belts below the bosom define the body. On the men, hose-clad legs are permitted to show under the bulky, midthigh-length tabardlike vests belted at the waist. The young men may favor that Florentine folly, the short-short doublet–but not in front of the duke.

The children are pretty miniatures of their parents; their dolls are miniatures of them. Skinny little dogs (now known as Italian Greyhounds) shiver by the fireside; the lucky ones are cuddled in laps. The company—including the dogs—exudes a chaos of perfume, though all are well-bathed.

Francesco’s guests pick up their cards. They are awkward to hold: large–nearly seven inches high–and thick. But what beauty! What richness! The exquisite figures are set off by gilded and embossed backgrounds. The cards and the setting have all the sumptuousness to be expected from one of the richest men in the world.

Francesco Sforza did not inherit his wealth and status. He fought for his place in the sun as a condottiero, a hired military commander. His prowess won him Bianca Maria Visconti, the only child of the duke of Milan. He fought again to claim the duchy when his irksome father-in-law named another man heir. Nearly three years after the old duke’s death, Francesco rode triumphant into Milan. The artist Bonifacio Bembo was one of Francesco’s supporters in the key town of Cremona. Loyalty’s reward was a steady stream of commissions.

The cards attributed to Bembo belong to the world of the painted book, a world that was passing away. Most playing cards were already mass-manufactured as woodblock prints, and the printing press would soon transform the world.

Bembo’s artistic style, too, was passing out of fashion. International Gothic art clings to the magical, iconic qualities of Medieval Gothic, even as its fluid lines break from the old rigidness and hint of what is to come: the sway of secular life in a world that is not necessarily a Fallen world.

Which is all very well, but the young man beside Francesco is more interested in a good marriage than philosophy. The woman must be well-born; the parents won’t have it otherwise. But it would be sweet to draw the Lovers, a couple holding hands under the auspices of Cupid.

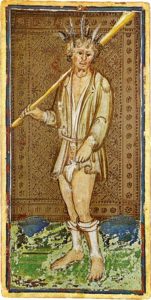

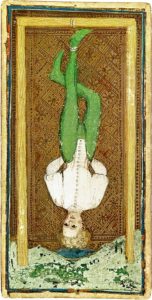

Bah. It’s the Madman. The feather crown and the club are his traditional accoutrements in art. But the youth has seen this fellow in real life, too, right out on the piazza in front of the cathedral, a living reminder of the need for charity. Like other such unfortunates, his bulging neck and doleful, addled eyes reveal a feeble mind.

For all his lowliness, though, this beggar, this madman, this Fool, is a trump card. Come spring, it is he who will lead the raucous Carnival parade into somber Lent.

The Carnival King embodies drunken abandon and the fertile madness of spring. But as his feather crown is plucked apart, all are reminded that revelry must be trumped by austerity, in honor of the Lord who trumped Death itself.

The Fool’s triumph is as short-lived as Carnival itself. His lumpy neck is goitered. Congenital hypothyroidism (CHT, previously cretinism) was endemic where mined (rather than sea) salt was used and where the soil was low in iodine. Its cause was unknown, but the outcome was all too familiar. Mental deficiency dooms the Fool to homelessness and the charity of those better off. More on the Fool and CHT

The poor are poor; the rich are rich: the medieval hierarchy holds. The four suits of the tarot correspond to the classes: swords for soldiers, batons for rulers, cups for clergy and coins for merchants.

By this scheme, peasants, laborers, and beggars do not even make the cut. (Nor do artists, for that matter.) No rule books survive from the time, but everyone would have known that, for example, the Emperor trumped the Fool card and the Empress, too.

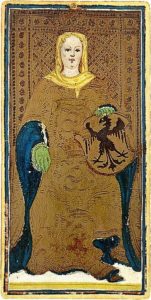

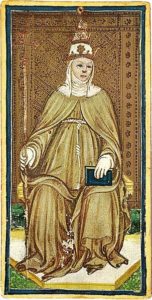

And the Popess?

Bianca Maria Visconti smiles at her favorite card. The gentle-faced woman wearing nun’s robes—and an incongruous papal tiara–is her ancestral kinswoman, Maifreda da Pirovano, leader of a cult that revolved around a mysterious and saintly laywoman known only as Guglielma. The saint preached salvation for all—even Jews and Saracens, and her followers considered Maifreda her vicar on earth, a female counterpart to the pope.

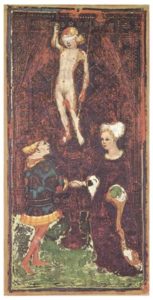

Does the duchess know that Maifreda was burned for such heresy 150 years ago? Maybe not. Evidence indicates that the Inquisition records were concealed. Or it could be that the Popess may be Bianca’s way of covertly defying the Papacy, as her husband and her ancestors have done overtly in battle. In fact—Bianca smiles again, wryly, though the next card could be considered inauspicious—a pope once cartooned her husband like so, hanging upside down as a traitor, when they were tugging a piece of territory between them.

Italy was not to undergo a mass religious reform, but the Middle Ages gave rise to scattered but fervent grassroots movements such as that of Maifreda and Francis of Assisi. Most were suppressed; some endure to this day. Spiritual urges changed as the Quattrocento progressed. The earthy ecstasies of the poor were eclipsed by the brilliance of more educated mystics.

But one trusty old symbol still has a say in the brilliant ascents and devastating downfalls of people and powers.

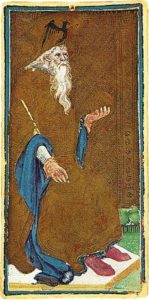

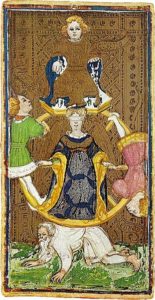

Francesco is not pleased to see the Wheel in his hand. At the top rides a crowned man holding the orb and scepter of dominion. Below, a ragged old man grovels. An eager hopeful rides up the side to take a turn at the top. He is oblivious of the unfortunate one heading down on the other side.

Then the corners of Francesco’s eyes crinkle; his sense of humor wins out. He’s ridden this wheel, sure; he knows its ups and downs. But he earned his scepter by the sword—not to mention wits and ability. He rose, and so will his sons rise, and his grandsons…

Little does Francesco know that the next generation will lose the duchy through mismanagement, extravagance and, after all, bad luck. He is yet striding toward the Renaissance with the resolve to bend the stiff Wheel into an upward spiral.

Just so, philosophers reach toward the heavens. The cash—and credit–of men such as Francesco Sforza and his sons fuels the swelling flood of translations and commentaries on Hermeticism, Kabbalism, and ancient texts. Literature, art and architecture are loaded with symbolic puzzles whose unravelment brings transcendental insight.

Some tarot scholars claim that the allegorical triumphs themselves were created as esoteric tools by Renaissance philosophers. However, the tarot images are rooted in popular Medieval imagery. The tarot sprang into, not from, the Renaissance.

A Triumphal Procession

Artworks of the Middle Ages have a mystical, emotional impact. Men and women love and fight, pray and die in rambling, weird landscapes whose proportion and composition are dictated by sacred narration rather than nature.

Renaissance art, on the other hand, is defined by naturalism, formulas of perspective, and the urge to unify wide-ranging schools of thought into a system animated by love and beauty.

The tarot embraces both: it is a triumphal procession bearing images of age-old wisdom from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, and on to our time. It speaks across the centuries, whether as Quattrocento portraits, symbolic riddles, or pictures in the game of life.

Even the most jaded of the triumph players fall under the spell of the sweet-faced allegories.

Praise and pleased laughter, flirtatious verse-making, guesses and gossip as to who is portrayed on the cards, demands to know where such cards can be bought, boastful laments about how expensive artists are these days. A philosophical type might reflect on a hand that includes a man and a woman clasping hands and a woman holding a star aloft.

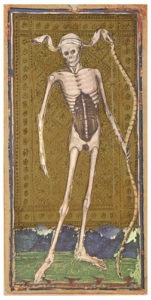

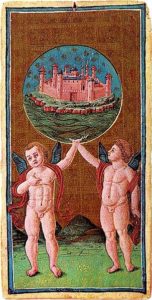

Hopes, intrigue—ahimé!—it’s the skeleton. How ugly—how unpleasant! Death intrudes on the fun to let everyone know: all these vanities so bravely built by art, intrigue, war, and wealth are as flimsy and fleeting as life itself. Indeed, look at the great palace of the World: a mere bubble held up by child angels. Like a dream, like an illusion; fragile—and yet, life is wondrous!

This article was first published in Fantasy Magazine

RENAISSANCE ITALY: GLORY, BEAUTY, GREED, WAR.

A POWERFUL HOLY WOMAN. THE INQUISITION….

A novel based on the true story of the Popess card of the tarot.

BUY: Signed by author, free shipping in US

BUY: bookshop.org | Amazon US | Amazon CA | B&N | indiebound

“Enchanting & richly historical, heart-wrenching & intoxicating.” —Stuart R. Kaplan, author Pamela Colman Smith.

“A storytelling treasure. The sights, smells, feel of Renaissance Italy seep from every pore of the story.” —Ron Andre, A Matter of Fancy