Maintain and mend was the rule in America through the nineteenth century. Wealthy people passed down worn, damaged, or out-of-fashion clothes, furniture, and dishes to servants or charity; less well-off people fixed things. Even after objects could no longer be used for their original purposes still more uses were found for them.

The original “garbage men” were recyclers. Housekeepers knew they were coming up the alley by their cries, just as every child heard the water-melon man coming along.

Each collector generally specialized. In his delightful description of 1870s “cries of Richmond,” Charles M. Wallace, remembered the “soap-grease man”:

“The only unmusical cry in the old days was that of the soap-grease man. Cooks and thrifty housewives would save the waste grease from the kitchen and sell it to him, when he would come to the back gate. He paid for it with soap-laundry soap, unscented, unpressed, cut with a fine wire into cubical bars and chunks. ‘Soap-grease! Soap-grease!'”

Bones as well as stove and fireplace ash also contributed to soap.

The “ragman” collected for papermills old cloth and scraps not used in the home for stuffing, rag rugs, quilts, and cleaning. Bones made soap and glue, as well as knife handles, dice, fish hooks, sewing accoutrements, pipe tampers, spinning tops, combs, and any number of gadgets. The bone articles might be ornamented with carving as well as incised and inked designs; whales’ teeth, called whale ivory, and whale bone are not the only materials used for scrimshaw, nor are sailors the only ones practicing the art.

Corncobs, cornhusks, and newspaper got re-used as outhouse “toilet” paper (Harper’s Weekly no doubt being a favorite in the South for this purpose). Newspaper also furnished kindling, wrapping, and bedding: “Pillows stuffed with papers an inch square, are good for Summer,” wrote Catherine Esther Beecher, in her 1842 A Treatise on Domestic Economy. Washing up water went in the garden. Horse dung became manure; vegetable waste might also find its way to the garden (usually chopped and worked into the soil, rather than composted), or it might be fed to chickens and pigs, as were other table scraps.

Bottles were re-used; the redoubtable Ms Beecher suggests using old bottles to store stain remover: “Send a Junk-bottle to the butcher and have several gall-bladders emptied into it.” (And for heaven’s sake, do label it clearly.) She also recommends saving tea leaves to prevent raising dust when cleaning carpets: “use damp tea leaves, or wet Indian meal [corn meal], throwing it about, and rubbing it over with a broom.” (Hopefully, gall-bladder bile removes tea stains.)

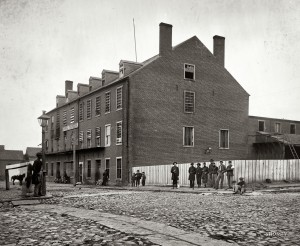

All this is not to say that people in days of yore generated no garbage. Refuse found its way to landfills as urban planners filled in valleys. Dumps existed, usually in the low-lying and, hence, poor areas of town. However, re-use as well as the absence of cigarette filters and product-specific paper and plastic wrappers kept streetscapes relatively trash free.

Sources: compost / bones / Charles Wallace’s street criers / Catherine Esther Beecher’s Treatise / photo Collection of National Archives

Very interesting!

Thanks, Becky!

Pingback:Palimpsest | JEAN HUETS