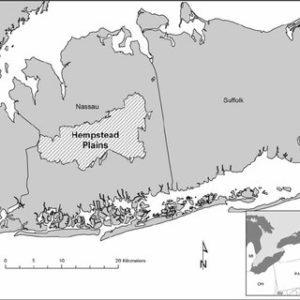

On this 200th anniversary of Walt Whitman’s birth, it seems only right to post about leaves of grass. Not Leaves of Grass, but actual grass, as in Hempstead Plains, Long Island. Not far from Walt Whitman’s birthplace, the Plains was one of the places he roamed as a child and youth.

Historically, Hempstead Plains encompassed about 60,000 acres in what is now Nassau County. A recent government study describes its remnants: “Hempstead Plains is a tall sandplain grassland community.… The soils are fertile, well-drained, silty loams and loamy sands. As with the maritime grasslands, the Hempstead Plains grasslands evolved with and were maintained by fires, some undoubtedly set by native Americans and others ignited by thunderstorms, over the last several thousand years.… The remnant Hempstead Plains are the only remaining example of this unique grassland community that historically was the largest sandplain grassland on the East Coast and is now the westernmost sandplain grassland between Cape Cod and New York City.”

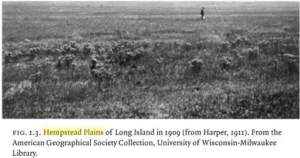

Hempstead Plains hosts many unique and rare species of flora and fauna. Development, use of pesticides, and the patchwork of ownership present conservation challenges. Farming and grazing also change terrain, even if not as quickly as development. A geologist noted as early as 1911, in an article on Hampstead Plains, that “once the soil is broken a very different flora, consisting largely of European weeds, comes in…” Predicting that “the continued growth of New York City is bound to cover it all with houses sooner or later,” the geologist enjoined scientists to “make an exhaustive study of the region before the opportunity is gone forever.”

A 17th century description of Hempstead Plains called it a “great curiosity,” the interior plains of the west not yet explored by European Americans. An 1839 history of Long Island gives an idea of the area’s original state: “The Hempstead Plain is notable in being a natural prairie east of the Allegheny Mountains. In its natural state it bears a rank growth of sedge grass. It was treeless when first discovered and was originally used as a commons for the pasturage of cattle and horses belonging to individuals and to communities.”

Grazing commons endured into Walt’s youth. He recalled: “More in the middle of the island were the spreading Hempstead plains, then (1830–’40) quite prairie-like, open, uninhabited, rather sterile, cover’d with kill-calf and huckleberry bushes, yet plenty of fair pasture for the cattle, mostly milch-cows, who fed there by hundreds, even thousands, and at evening, (the plains too were own’d by the towns, and this was the use of them in common,) might be seen taking their way home, branching off regularly in the right places. I have often been out on the edges of these plains toward sundown, and can yet recall in fancy the interminable cow processions, and hear the music of the tin or copper bells clanking far or near, and breathe the cool of the sweet and slightly aromatic evening air, and note the sunset.”

The Plains also bred equine enthusiasm. The 18th century history states that Hempstead grass made “exceeding good hay,” and the terrain offered ideal racetracks, “with neither stick nor stone to hinder the horse heels, or endanger them in their races, and once a year the best horses in the island are brought hither to try their swiftness, and the swiftest rewarded with a silver cup.…” Though Walt doesn’t mention riding horses, he proudly described his mother as “a daily and daring rider” in her youth, and was an enthusiastic spectator at horse races.

The Plains’ lack of sticks was due to the scarcity of trees, a characteristic of prairies. The Hempstead Plains was bordered with forests, though, mostly oak, that were used by settlers like Walt’s ancestors for fuel, lumber and windbreaks. A 1911 geologist noted that much of the area was still “in a state of nature,” despite being fairly well settled and “within the zone in which it is profitable to haul farm products to New York by wagon.” Walt recalled riding with his father to Manhattan with a wagon full of farm produce. (Unfortunately, farming did not bring profit to Walter Whitman, Sr.)

Hempstead Plains formed the cradle of a family friend who was one of Walt’s heroes, the Quaker reformer Elias Hicks. “My great-grandfather, Whitman, was often with Elias at these periods [before the Revolutionary War], and at merry-makings and sleigh-rides in winter over ‘the plains.’ How well I remember the region—the flat plains of the middle of Long Island, as then, with their prairie-like vistas and grassy patches in every direction, and the ‘kill-calf’ and herds of cattle and sheep.”

Walt recalled rural Long Island not as undisturbed, but rather as a place where human purposes had not entirely displaced nature, all for the good of nurturing a child’s body and spirit. “Numerous copses and hedge-rows conceal the cultivated fields and the steadings,” he wrote, “so that the prospect is that of a wild, scarce-cultured scene, imparting a sense of rude nature and free growth to the mind.”

WITH WALT WHITMAN, HIMSELF: IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, IN AMERICA | by Jean Huets

“A true Whitmanian feast—for the intellect as well as for the eyes.” — Ed Folsom, editor Walt Whitman Quarterly

Amazon | B&N | bookshop.org (supports indie booksellers)

signed copies, free shipping order from Circling Rivers

“A beautiful book of windows onto the life of Walt Whitman…. From the clear ringing prose to the fascinating photographs and colored illustrations of the great poet’s life we find the man anew—standing in his time and looking straight at us. [Huets] has made a book of marvels and I can’t put it down.” — Steve Scafidi, Poet Laureate, Virginia

Explore the fascinating roots of Whitman’s great work, Leaves of Grass: a family harrowed by alcoholism and mental illness; the bloody Civil War; burgeoning, brawling Manhattan and Brooklyn; literary allies and rivals; and his beloved America, racked by disunion even while racing westward. Over 300 color period images immerse the reader in the life and times of Walt Whitman.

SOURCES: Annual Report of the American Institute, on the Subject of Agriculture (p 690-91) here | Significant Habitats and Habitat Complexes of the New York Bight Watershed: Long Island Grasslands here | Harper, Roland. “The Hempstead Plains: A Natural Prairie on Long Island. Bulletin (formerly Journal) of the American Geographical Society … Volume 43, 1911. pp. 351–360 here | Color photo by Friends of Hempstead Plains here | 1909 photo via Bill Bence, Long Island Catalog; the blog post includes a contemporary description and history of Hempstead Plains. here | Map here

The Plains are great survivors, aren’t they> Lovely piece.

Thanks!

Pingback:Essay Publication: Public Domain Review | Hound: The Art of the Dog